Lonnie Mendes

The Secret Section.

I’d studied everything in Ken Halberson’s suitcase, and the story seemed to be at an end. Days, weeks, months of my life inhabiting someone else’s mind and life and experiences. I felt I knew Ken as well as I’d known anyone in my life. I’d traced every lead I could find, exhausted every trail, searched out Halberson’s life story online, done my due diligence, followed the tale wherever it led. I’d told Ken’s story. Ending it all with Ken kneeling, beaten, on the scarred face of the barren New Mexico desert, pounding the ground with the Mickey Mantle ball in hand, and accepting that he is the one that destroyed Nowhere… and, well, that should have been the end of the story. I’m a Russian literature enthusiast. I like dark endings that still somehow teach us a more universal truth. I loved that, at least to me, Nowhere was a great metaphor for America (or any other place for that matter,) where something is constantly under attack by skeptics who want it to be more perfect, and imperfect, and who would destroy it because it is both and neither.

Halberson, if we believe the online legend, was a tragic character. He disappears from the view of the world from 1954 to 1961. Then reappears. We know now that he spent several months of 1954 in Nowhere, New Mexico. He was almost certainly a functioning alcoholic before he went to Nowhere. Knowing Halberson personally, as we all do now, he spent many of the silent years searching for Nowhere. Searching for Kate. Looking in the bottom of a bottle for everything he’d lost. Straining to carry what could have been and pulling on every thread until even what little he still had came undone. Then, there was the inevitable collapse. Rehab. Some level of recovery.

He resurfaces from those lost years, according to the record, in 1961 when he goes to Cuba on his own dime to cover the growing tensions between communist Cuba and America. He meets and interviews Fidel Castro, and he’s there during the Bay of Pigs invasion in April and returns to Schenectady to write his definitive book on the debacle. He’s awarded the Pulitzer Prize and his book becomes a runaway bestseller. After that, he writes a few more non-fiction books, mostly on baseball or politics. Perhaps he’d gotten sober after he came back from Cuba, or at least had moderated his drinking, but in 1974, Halberson is killed in a car wreck in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Drove off a mountain.

However, shortly after I finished (or thought I finished) the book, I was forced to admit, as The Dude says in the film classic The Big Lebowski, “New shit has come to light.”

I’d given a copy of the manuscript to my friend Wes, the operator of the Bonneville store in Coleman, Texas. You’ll remember him. He’s the usually good-natured but sometimes surly guy who sold me Halberson’s suitcase in the first place and started me on this road. I stopped in to see Wes, just as I usually do once or twice a week, and I asked him what he thought about the book.

The Bonneville is a mid-century modern furniture store in Coleman, Texas that consists of Bonneville (the vintage used furniture part) and Bonnevinyl (the old vinyl records store.) I walked in through the Bonneville side and saw Wes talking on the phone and in the midst of an animated conversation.

“I’m just saying that I’m tired of cake. That’s it. I’m just tired of it. I know you like to make cakes, I know it, and it’s something you enjoy, but… yes… frankly, I’m just so sick of cake. I’ve just had it! I can’t eat any more. Why can’t you, you know, get into cooking crab? I love Dungeness crab. Crab makes me happy. Cook some Dungeness crab every day for a while. Let me get sick of that. Just no more cake. No… no… not forever. A cake every once in a while… no… that’s fine. I’m not saying forever. I’m… yes… yes… ok. Talk to you later.”

I looked at Wes, trying not to laugh.

“What’s up?” Wes said.

“Did you get a chance to read the manuscript?”

“I did,” Wes said. “It’s good. But it ends kind of dark, don’t you think? And did you use the stuff in the back section of the suitcase? The document area?”

My heart thudded in my chest. “What back section?”

“In the 50s, some of these suitcases, not many but some, were used by traveling salesman and diplomats and whatnot. So, they had a, you know, kind of secret document area in the back of the case. People would put passports or cash or stuff they didn’t want their wives to find in that area. It’s behind the liner in the back.”

I was stunned. Is it possible I’d missed something? “Are you saying there were notes or documents in the back of Halberson’s case?”

“Well, yeah. I looked there because I’m not an idiot. If there was money or stock certificates, I would have known it before I sold all the useless stuff.

Nothing I wanted there—just more notes—so I left it alone.”

I didn’t even say ‘thank you,’ or ‘goodbye,’ I was out the door and back in the car and speeding toward home.

***

I found the notes exactly where Wes said I’d find them. Why Halberson put his last notes on Nowhere in the section behind the liner, I don’t know. But how his suitcase ended up in a mini storage in Albuquerque and then probably in someone’s attic for decades, and how no one threw out the notes over the intervening years when they sold the case, or how the case ended up in Coleman, Texas… I don’t know any of that either. Deus ex machina. God in the Machine. Or maybe this story was supposed to be told.

The notes I found behind the liner were short and scattered. Often several years passed between them. They contributed texture, but most of it was stuff I already knew or suspected. All except for one of the documents. That one was a mind-bending game-changer, but I’ll get to that in its place.

Ken went on a search for Kate and for Nowhere. After he left the desert with the knowledge that Nowhere had been erased, he didn’t go back to Schenectady. Not ever again, as far as I know. He went to New Orleans. He believed his best chance for finding Nowhere was to search for a thread on Lewellyn Bonaventure. He took an upper floor apartment just outside of the Quarter and drank every night in some bar or club, listening to jazz, talking to jazzmen. He had a girl now and then, but never for long. Every night he’d stay out drinking ‘til close, which sometimes was 4 a.m., then walk (or stumble) home to his apartment. In the mornings he’d stay in bed until noon or 1 p.m., drink coffee, then he’d work or drink some more. His ‘pay the bills’ job at the time consisted mostly of ghostwriting. He did some stringer work under the byline of Paul Langtry, and I was able to find some magazine articles he’d written under that name. He wrote a few fiction novels, I have some handwritten receipts from an agent for payment, but he did so as a ghostwriter. Without another miracle, I’d probably never find which ones he’d written. He took trips, and it was on these trips that I reckoned he was looking for Nowhere. He went to Albuquerque a dozen times between late 1954 and 1960. He also flew to Costa Rica, Brazil, Romania, South Africa, and Mexico. He was in Canada for two months in 1958.

He did extensive searches trying to find Abe Mendoza and Maryweather Copeland and was constantly looking for and interviewing anyone he could find with the Laird last name. None of this, it seems, bore fruit.

He spiraled into even deeper alcoholism, and I know this because in early 1959 he checked himself into a rehab clinic in Metairie under the Paul Langtry name and was there for eight weeks. After that, his notes are fewer, but more cogent, and written with a steadier hand. Typically, his notes from the time read something like this:

Got a lead on a Jonathan Laird > Kentucky. Drove and stayed 3 days in Somerset. Nothing. No connection.

3/7/1957 Met a trumpet man playing at the 500 Club, Leon Prima’s place. Nothing substantive. He said he played with Dick Hager before the war, knew he was a homosexual, but lost contact after the war.

As I’ve mentioned on several occasions, at some point in late 1960, after the election of John Kennedy, Halberson decided to get back into the writing business. Under his own name, and paying his own way, he flew to Mexico City, then from there to Havana under a special journalism visa issued by the Mexican government and approved by Castro. His book on the Bay of Pigs invasion from the perspectives of both Castro loyalists, and Cuban ex-patriots in Florida and Texas was published in 1962, first serially over several months in LIFE Magazine, and then by Scribner. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and was the New York Times bestselling book at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of ’62. You know most of the rest.

Then there was this. The game-changer.

The final document in the cache in the back of the Samsonite was in an envelope from Thompson at LIFE and addressed to Paul Langtry, (so Thompson knew about Halberson’s alias.)

It was a letter from none other than Kate Laird, dated in late February of 1974. Just months before Halberson’s fiery death at the bottom of a mountain in New Mexico.

***

Dearest Ken,

The time has come at last to reconnect with you, and I hope this letter finds you well. It’s been a long, long time.

I will not fiddle around with niceties. John Lee is ill and doesn’t have much longer, I’m so sad to say. All is forgiven. He’d like to see you, if it is possible, and to be honest, I’d love to see you too. I will understand if this is not desirable or practical for you. If you are interested, go to Albuquerque. Check in to the Mayflower Motel west on the Interstate. Someone you know will be in contact.

In dearest and most sincere love,

Kate

***

Just as I was studying the letter from Kate, I received a message from Wes at Bonneville asking me to stop by.

“How’s it going with the book?” Wes said when I walked in.

“Just trying to figure it all out. I might have something big, but I don’t know where it’ll go.”

“Well, I don’t know if it’ll help, but I have something to show you.”

I drove to town and we walked through the mid-century seating areas and vintage furniture displays and back to the vinyl section. Wes thumbed through a stack of albums, and then pulled one of them out and handed it to me.

Dick Hager and His Mighty Men

“Wow,” I said. “Where did you find this?”

“It was here all along, I guess,” Wes said. “I don’t keep these things in any kind of order. That would take work. But I was looking for a different album for an online customer and I ran across this. Thought you might find it interesting.”

“Wow,” I said again.

I studied the cover. I don’t know why I didn’t go on a search for the cover when I was writing the book, but I guess I was so completely underwater studying Halberson’s notes and laying out the whole timeline and story of how it really happened, that I never thought of finding the actual album. Seeing Dick Hager, who is John Lee Danner and Lew Bonaventure, in an actual photograph was surreal to me. I studied the other faces in the band, picking out the ones I knew to be Carlo Rocca the drummer, the man Halberson called Verne Powell, and even Cat Ivie on the trombone.

“Do you see it yet?” Wes said.

“See what?” I said. “I mean, I see all the people from the book.”

“Really? I don’t think you do.”

I scowled. “Listen, Wes. What am I supposed to see?”

Wes pointed a finger to the clarinet player in the front row, a darker-skinned man, maybe Italian or Greek or Spanish, with dark black Ricky Ricardo hair and a well-trimmed black mustache and beard. “Do you know who that is?” Wes said.

“Should I?”

Wes flipped the album over to the liner notes.

“Clarinet – Abraham Mendes.”

“Who is Abraham Mendes?” I said.

“How do you write books? Abraham Mendes? C’mon! Abe Mendoza!”

“Wait. No.”

“Think about it,” Wes said. “In your book, you mention how the record company execs made Bonaventure change his name to Dick Hager because Bonaventure was too Cajun. You don’t think ‘Mendoza’ might have been a tad Hispanic for 1954?”

“Louis Prima was hot in 1954,” I said.

“Louis Prima was Italian. Like Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. Italian was hot at the time. So was Greek. Spaniards too. Dark and mysterious. They changed his name, man. That’s Abe Mendoza.”

I shook my head. “Sounds good, but here’s what we’d have to believe to accept that. We’d have to believe that Ken Halberson, an award-winning war correspondent and journalist, looked at this same album cover twice and didn’t recognize his own friend?”

“You wrote a whole book featuring the guy and you didn’t see it until I told you.”

“Good point, but I wasn’t Mendoza’s friend.”

Wes laughed. “Friend? Maybe. But he’d spent one night with the guy drinking until they were drunk, and then saw him maybe three other times for a few minutes each time… also when he was drinking or drunk. And Mendoza was older when Ken met him. Probably heavier eating his wife’s cooking every day, and her forcing him to eat. Hair had turned gray, maybe didn’t have the beard. Grayer mustache.”

I looked at the album cover again. Abe Mendoza as Abraham Mendes?

Maybe.

Wes smiled. He was enjoying giving me a hard time. “I looked up Abraham Mendes online. I used this thing called a Google. It’s a great research tool, you should try it. Anyway, Mendes lived out his life in Albuquerque of all places and died there in 1980. His family probably still lives there.”

I was shaken. I told Wes ‘Thank you’ and offered to pay for the album.

“Just keep it. No one but you would ever buy it. So, what’re you going to do now?”

“I guess I’m going to Albuquerque.

***

Ken checked into the Mayflower Motel outside of Albuquerque and immediately fell back into a few bad habits. He’d never completely given up drinking, even after his stint in rehab, but he had moderated his intake. He rarely drank alone anymore, and even when he did drink in public or with friends, he kept it reasonable. Sure, he’d messed up a few times, fallen hard, but not many, and he felt better about his ability to control it. But being back in Albuquerque, knowing that Kate sent for him, he wasn’t able to sit there in the room without drinking to steady himself.

He was 50 now, and not in bad shape. He’d focused on his health more after returning from Cuba, and for the last ten years, he’d maintained his body better than he had for the first 40. His eyes were clearer and his mind had regained some of its youthful vigor. He still liked to drink. He just didn’t prefer to be drunk anymore.

He’d asked the cabbie who picked him up at the airport to stop at a liquor store and he purchased a nice bottle of scotch and a pack of cigarettes. The parallels with his first time in Albuquerque were sitting heavy on him. That drive around the city at night twenty years ago looking for a bootlegger. The nervous churn of butterflies, not quite as bad as on the LCVP off Normandy, but still there. That night twenty years ago he was curious, but that curiosity was not mixed with trepidation. Now, with the possibility of finally seeing Kate. Well, he needed to drink.

He’d moderated his drinking but he’d totally gone off cigarettes after Cuba. Hadn’t touched one in years.

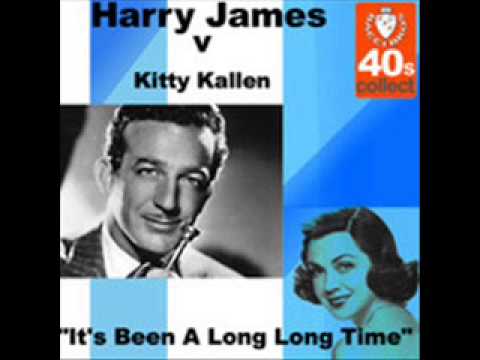

He started sipping the scotch after 5 p.m. and didn’t allow himself to get too drunk. He was nervous, hands shaking and not from the booze, so he lit a cigarette and inhaled deeply, feeling the old familiar calm settle over him. He let his mind take him back once again to his small apartment in Nowhere and here he opened the Samsonite and fiddled with the contents. Nostalgia. That open wound once again. He could almost hear Kate’s beautiful voice singing It’s Been a Long, Long Time. In the distance. Not quite here. He wondered what Kate was like now. Had she married? Did she have children? The scotch was doing its work now, slow and easy. He knew what her hand felt like, and her lips brushing his neck. The burn warmed and his mind clicked into another gear. The background blurred, but just a tad and the cigarette smoke swirled like translucent silk, upward, dissipating as it rose. He inhaled and it was like Kate’s perfume was there, barely, just a hint of it mixed with the stale air and cleaning supplies from the room, and then all of that faded but her scent, and they were standing on the pinnacle of the city, looking out over the lights of town while a soft breeze touched their hair and the sounds of a quartet down below rose up to meet them, a Harry James song.

And then there was a knock on the door that broke his reverie, and he was back in a motel room, a lonely fifty-year-old man drinking and smoking a cigarette.

Another knock and he got up to get the door, opened it, and saw a welcome face from his past.

Abe Mendoza.

***

That last section is a weird thing if you’ve been paying attention. Heretofore, I wrote from Ken’s perspective, but it was based on his explicit notes, sometimes long prose sections, written drunk or sober, depending, describing what he’d been doing and seeing. But I would put Ken’s scratchings into my own words, sometimes adding needful details but mostly transcribing Ken’s experiences for you just as they happened. But here, it seems, is something new. As far as you know, the last thing we have from Ken Halberson is him finding the letter from Kate asking him to go to Albuquerque and wait. What, then, is the deal?

As far as you know.

This is a form of historic revisionism, wherein the historian alters his description of history to include and allow for information learned subsequently (in the scholastic form of ‘history’ perhaps this subsequent data is true, perhaps not, perhaps it is made up altogether, or an agreed-upon myth founded in new social and cultural dictates.) The point is that this previous section, with Halberson drinking in the motel and Abe Mendoza coming to the motel, is information I learned later, but it belongs here in the story.

As for me, I started my research into Abe Mendoza being Abraham Mendes online. I found several people using the name ‘Mendes’ in Albuquerque, and I sent messages on social media to as many as I could locate asking them if they were at all related to a man named Abraham Mendes, born 1907 or so. Almost all of the ones who replied to me were not connected. In the meantime, I made preparations to drive to Albuquerque at some point. Didn’t know when. I figured it was long past the time when I needed to go there myself.

Eventually, a man named Lonnie Mendes responded to me, and over a few days, we had conversations about Abraham Mendes. Indeed, this Abraham, his grandfather, had played in The Mighty Men in the 1940s and had known and worked for Dick Hager, the bandleader. Lonnie was happy to talk about his grandfather, Abraham’s skill on the clarinet, and his memories of the man.

I tried to direct the conversation in a way that would allow me to ask if Abraham Mendes was Abe Mendoza, but Lonnie was quite adept at directing questions back at me. He asked about my writing and the next day when I talked to him online, he’d either read or listened to a few of my books as audiobooks. He asked about my life, my family, and asked if he could read what I was working on at the time. I threw caution to the wind and sent him a copy of this manuscript, the first twelve chapters of the Nowhere, New Mexico book. It was two days before I heard back from Lonnie. And then there was this…

You should come to Albuquerque if you want to learn more about the Abe in your book. If you are clever, you will find me.

***

Ken and Abe embraced at the door like long-lost brothers.

“Amigo! So glad to see you!”

“You too, Compadre,” Ken said. “Come in. I have scotch.”

The two men drank scotch and talked for hours, draining the bottle. Abe had many questions for Ken and answered very few. Ken knew: He’s sizing me up. Just like last time.

“What are you writing now?”

“What do you love, my friend?”

“What would you do if you could go back to Nowhere?”

“How has your philosophy changed in twenty years, Amigo?”

“Who will miss you if you could go there and never come back?”

That last question is one that hurt a little bit. Ken knew the answer at once. No one. Nobody would miss him. Sure, his editors might miss having a sure thing, someone they knew. But he had no wife, no children, no family. Ken Halberson was alone in the world.

“If you could go right now, friend, would you be writing a book? Just there for what you could take? Or would you want to stay there forever?”

“Forever,” Ken said. “No doubt about it.”

Abe nodded. “And though Kate might be there, and very eager to meet you, there is no promise that she is for you, you know this? She has done very well without you, sad to say.”

“I understand.”

“And you could forsake all of this. Leave and disappear?”

Ken took a long draw on his cigarette. “All of this?” He looked around the hotel room. “Absolutely.”

“Then come, Amigo,” Abe said. “There is something we must do.”

***

I arrived in Albuquerque and it was the Christmas season and many homes and businesses were lighted for the holidays. My motel was not far from the airport. I spent the first couple of days doing research on Ken Halberson’s death there in 1974.

At the library, I was able to find the records of Halberson’s accident. It was April of 1974 and Halberson was driving in the Sandia Peak area and, according to the reports, his car slipped off the mountain, plunged a hundred feet or more, and he was killed. When it was learned that the dead man was a famous person, a Pulitzer Prize winning author, there had been a spurt of interest in the story. Some of the policemen who’d responded to the tragedy were interviewed.

There was the usual speculation. “Well, you know, he was famous for being something of a drinker. And there was an empty bottle in the car.” “He was in and out of rehabilitation clinics for alcoholism, you know. It happens.” “He wasn’t married. Probably despondent. Who knows?” “Maybe it was suicide.”

The more I looked into it, the more suspicious I became. First, Halberson’s body was cremated faster than usual. Within days. Long before any local authorities knew that he was a famous author. No wife, no kids, no family, who was going to argue? But there were other serious questions if you knew everything that I knew about Ken Halberson. It was Halberson’s car, no doubt about that. Identified by the cops. But the man who died when the car went off the mountain and caught fire at the bottom was said to be ‘of normal height, and obese.’ Ken Halberson was neither. He was a tall man, well over six feet, and he was fit most of his life. Never obese. I dug deeper into the microfiche records of the local newspaper, and there’d been another death reported a few days earlier than Halberson’s, an indigent man who’d died from a heart attack in a homeless shelter. That man’s name was Lou Brinkman. I looked into the records and there was no paperwork indicating that Lou Brinkman’s body had ever been buried or cremated. A search on the Internet of obituaries and burial spots turned up no hits that matched Lou Brinkman on those dates in April in 1974.

Did Halberson fake his death? Did he actually go back to Nowhere and stay there?

***

I gave up looking into Halberson’s death because I was at a dead end. I started looking for Lonnie Mendes. Another day searching social media and online yearbooks from Albuquerque and I was pretty sure I’d found him. I scoured his social media posts and found out in a comment on one of his posts that he bartended at a speakeasy in town, and that as part of the vintage schtick, in order to get into the speakeasy, you had to ‘like’ their Facebook page, and if you did you’d get a private message with the password for that night. I found the place and hung out there a few nights drinking dirty martinis and the occasional old fashioned. On my third night there I identified him from his social media profile picture and when I ordered my drink I asked him if he knew how to make an Abe Mendoza. He smiled at me and nodded and when he brought my bill I noticed that it had already been comped and on the back of the bill was an address and the note: Noon Tomorrow.

***

Abe had it all worked out, how I’d disappear from this world for good, and he laughed when he told me he’d been wanting to kill off Ken Halberson for twenty years now. Abe knew people and he’d been working this gig at shepherding people to Nowhere for a good long time so was an expert in the cloak-and-dagger stuff. He already had a stiff ready to go and promises from other friends that there wouldn’t be much of an inquiry into my crash, and frankly, I was looking forward to reading my own obituaries like Hemingway had back in January of ’54 when he’d been involved in two airplane crashes over just a few days and the world’s press had pronounced him dead before learning that he’d survived. Hemingway and I had something else in common, both of us being winners of the Pulitzer, but he also won the Nobel Prize for Literature and was a great novelist, so his premature death would garner more print and bigger headlines than mine would.

We loaded the body into the front seat, said a few words for the guy who we didn’t know and who was scheduled to be cremated by the city anyway, released the emergency brake, and pushed the car off the side of a mountain. Bam. Bob’s your uncle, and it was done. We drove back to Abe’s house and I was reunited with his wife and she tried to feed me like she’d done back in ’54, which was nice.

“Amigo of mine, this time things will be different.”

I nodded, mouth full of pork and potatoes.

“Not just different in the way we must go to get there, quite perilous, but different in that you, hopefully, have learned a lot about yourself in twenty years. Perhaps now, after so much pain, you are ready to be happy, Si?”

“Yes, sir,” I said. “I’m ready.”

“Our friend John Lee is not in good health. He hasn’t long, they say.”

“That’s what Kate said in the letter.”

Abe indicated to me with his fork. “John Lee likes you very much. He hopes to see you soon. He told me this.”

“When do we go?”

“We go now, Amigo. But this time, it will be different.”

Abe pulled a bottle of pills out of his pocket. “You will take three or four of these when we are in the car. They will knock you out. Better that you know nothing of the way this time. Insulate you against your former… tendencies.”

I took the pills. “Do I take three or four?”

“Probably for you? Four. You are a big hombre.”

***

At one point, Ken stirred a little in the backseat of the car, but not for long. He didn’t know how long they’d been driving, but he had the momentary impression that they were driving east. But he was groggy and had no way of knowing. Then he was out again. He heard voices once or twice and felt himself being taken from the car at some point and strapped to a gurney. That was all he remembered, and he didn’t know what was real.

He woke up with bright sunlight shining through cracks between the curtains and he struggled a little to stand before walking to the window and throwing open the curtains. And that’s when he saw it, something so familiar it made his heart leap. The sign was tall, turquoise and orange:

Vacation in Nowhere Motor Inn

Ken Halberson was home.

***

I found Lonnie Mendes’ home and rang the doorbell right at noon. Lonnie answered the door dressed casually and we walked through the house and out a sliding glass door onto a patio bathed in sunlight. We sat and Lonnie pulled two beers from a soft-sided cooler and handed me a cold one. We twisted the tops, clinked our bottles, and each took a swig.

“I liked your story, man,” Lonnie said. “I learned a lot about you.”

“About me?” I said. “I’m barely in it.”

“You’re all through it.”

I shrugged. “I guess.”

We talked about the book, and Lonnie asked a lot of questions. He didn’t answer many. I told him my theory that Ken Halberson had faked his death with the assistance of his grandfather, and Lonnie just smiled. He told me the story, much of which you just read, but he told it speculatively. Like, ‘if it happened, it happened like this.’

After a few hours of chatting, and quite a few beers, I asked the question I was there to ask.

“Where is it?”

“Where is what?”

“Nowhere. Where is it today?”

Lonnie stood and took his beer and walked to the edge of the patio, looking off into the distance. He stood like that for some time, as if he was pondering something or praying. Then he turned to me.

“Perhaps someday you will go there yourself.”

“Perhaps? How?”

“Nowhere has a way of calling you.”

***

It was a beautiful spring that year, 1974, and as we drove through town the electric blue of dusk settled down over a city that had changed very little in twenty years. Nowhere had been rebuilt almost identically to how it existed in 1954, and why wouldn’t it be. The streets were the same, same names, same intersections, and the houses, most of them built when the town was reconstituted, were much the same as well. Here and there some newer model houses, not much different in style, had been built, but overall the town was shockingly similar to how I remembered it. The signage in some places was updated and more modern, and the cars were mostly 60s and 70s models, but… it was Nowhere. I felt like I was still high from the drugs, but I wasn’t. My heart sang.

We went and visited John Lee. He was living in the house I knew as Bonaventure’s and he was in a hospital bed in the big round room when I saw him. He smiled.

“Hello, old friend,” he said. “Welcome home.”

***

I made it back home, and now I’m writing up the rest of this. The end of the story, as far as it goes. My meeting with Lonnie Mendes had given me a lot to think about, and he’d tied up some loose ends as to what became of Ken Halberson and about his return to Nowhere. Now, looking into this glowing screen in a darkened room and knowing that we’re nearing the end, I’m having mixed emotions. But maybe that’s the way it always is. Maybe you never want to leave Nowhere.

***

We pulled in front of the Downtowner. The grand old lady still sparkled with charm and elegance, not touched, like so many urban buildings in so many other cities, by decay and decline. She was only twenty years old, but she was ancient and beautiful. The valet took the keys from Abe and handed him a ticket and a doorman held the door for us as we entered.

I heard the music first, soft and low, coming from somewhere, and we entered the elevator and the operator took us up to the top floor. The swoosh of the door opening that I remembered so well, and we entered Bix’s. A small jazz band played dinner music and a few couples embraced and moved together on the dancefloor.

“Go on,” Abe said to me. “I’ll get us a table, Amigo. Someone is waiting for you on the terrace.”

I almost couldn’t walk; I was so nervous. Scared. But I did walk. Through the restaurant and out through the glass doors and onto the terrace. Kate wasn’t there, and I looked everywhere, just a few couples holding hands and talking, and then I saw the spiral stairs leading upwards and I rushed to them and grabbed the handrail, pulling myself upward hoping my old leg wouldn’t give out on me.

Up to the top, a nervous glance around, and then I saw her, her back to me, hands spread wide on the railing, looking out over the town at the last glow of the day, orange-yellow shading upward to purple and then dark blue on the western horizon. The town was an electric backdrop, sparkling but blurred because my eyes were on her. Her dress was blue with a white belt and her hair was pulled back in a ponytail like the first time I ever saw her, and I knew her like I knew my own face in a mirror. Like no time had passed. I didn’t breathe for fear a noise might make her disappear. The music swelled in my heart and mind and I inhaled at long last, taking in my first real breath since I’d arrived in Nowhere. Maybe it was my first real breath since I’d left twenty years ago.

“Well, Mr. Halberson,” she said without turning around. “It’s been a long, long time.”

***

“Nowhere has a way of calling you.”

Does it?

As for me, I don’t know what I’ll do. Knowing that Nowhere is still out there may be enough for me.

Then again, maybe it won’t.

THE END

Downloads

PDF Version

Mobi Version

ePub Version

Finally got a chance to finish Nowhere New Mexico. This was a very unique story and I really enjoyed it. I can’t wait to get a physical copy.