Dick Hager

Fort Knocks.

Everything Kate said was true. There was gold, and even now as you read this you cannot conceive of how much gold there was. However much you are imagining, there was more than that. Stacked on steel pallets because of the tremendous weight, bricks of gold piled two feet high with pallets lining the side of the tunnel and as far as Ken could see. He began running and he knew not why. This was not a charade. This wasn’t Operation Fortitude. No one would have ever taken a con this far. He ran and ran and after he couldn’t run anymore the pallets loaded with gold kept going and going like there was no end to it. Along the base of the tunnel was a pipeline and Ken knew this was the fuel pipe bringing petrol into the area from Gallup, and at one point it bent and went through the wall, probably heading to the area far up above where the fuel truck would be loaded for runs into Nowhere.

Gasping for breath and leaning from the strain, Ken nearly collapsed with the weight of it all. Bonaventure had found gold. More gold than had ever been in Fort Knox, even after the government seized all the known gold back before the war.

“It’s overwhelming,” a voice said from behind him.

Ken’s chest heaved and he straightened and turned slowly to find John Lee standing there, arms crossed.

John Lee Danner.

Dick Hager.

Lew Bonaventure.

“Lewellyn Bonaventure is my given name,” he said. “I changed it to Dick Hager when I got into music, or, when I was forced to change it. The piranhas in the music biz said that Bonaventure sounded too Cajun. At that time jazz was becoming swing and the Yanks were trying to shake off that down south old-school hot jazz stuff. Trying to make it more cosmopolitan. More pop. I’m not from Kentucky, another little white lie to protect my identity. I was born in New Orleans and learned my jazz there on the street corners and the flophouses and on the riverboats, and I went to Chicago and then New York like most Cajun coonasses who could play did back in the day. Louis was one of the only ones who could get away with being pure New Orleans in the big bands. Bix was dead and Whiteman was king and Goodman and the Dorseys and Glenn Miller were on the rise.”

“Why John Lee Danner, then? You’d already changed your name once.”

“The music business is a parasitical farce, from Tin Pan Alley to the pernicious scams perpetrated on young talent by the accountants and execs. Fats Waller was economically raped all of his life, selling hundreds of his songs for pennies just to get by. A lot of those songs never got his name put on them. The colored songwriters had it worse, but it was bad for all of us. Most of us die without a dime to our names. New York is an antichrist island of devils where musicians go to be sucked dry, and Hollywood is no better. When I quit, I quit for good, and I didn’t want my ‘fame’ or history with me anymore. Tied around my neck. Dick Hager died just like Lew Bonaventure had before him.”

“Why not just go back to Bonaventure?” Ken said.

“Lots of reasons,” Lew said. “I’m what they call a ‘fairy’ out there in the world. I have baggage. My own private proclivities that ain’t no one’s business but my own. You have yours too, friend, but mine don’t hurt people as yours do. Anyway, all of that stuff was being held over my head by the powerful music execs and record companies. If I kicked up a fuss, demanding a new contract or royalties that were owed to me, they would have ruined me. Scandal, you know? And they were the ones who gave me the name Dick Hager in the first place, so they knew I was Bonaventure first. They’d have kept coming after me as Hager, so I became John Lee Danner, a new man, the name a conglomeration of names that mean something to me. That’s who I am now, and that’s what I go by. Anyway… who gives a shit? It’s really my business, Ken. I’m just telling you because I once liked you very much. I thought you might make a go of it in Nowhere. I thought you were one of us.”

Ken shook his head. “I don’t even know what that means.”

“Someday you will. Someday soon and for the rest of your life, and you’ll regret what you’ve done here. Frankly, I feel sorry for you.”

“Is that a threat?”

“You’re the only enemy you have, Halberson.”

“So… Copeland?”

“Came out here in ’46. The story is that Hoover sent him to figure out if I was some kind of spy. They wanted to know what some old prospector was doing in the nowhere drylands sniffing around near their precious secret facilities. Copeland came to check things out. He did. Figured out who I was, but we hit it off anyway. Kindred spirits. We drank and laughed and dreamed of what kind of place we’d like to live in. He made excuses to stay for a while, and when I found the gold, Maryweather became my angel. He had connections. A lot of military and civilian specialists in the right places who knew he was a hero in the war. Maybe even won it for us, they say. Eventually, it became obvious that he had to tell them something and go back to his real job, so he told them I found gold but not enough to amount to anything. Then he went back, bided his time for a few months, then retired and came back here.

“Now we had the resources to make a go of building something real and special. Copeland helped hide the place. Got a guy in treasury who skewed the numbers so we could drip out the gold—all over the world—and not raise any suspicions. He had money too, a ton of it. Inheritance from unscrupulous ancestors. This whole world is a hive of mendacity and theft. Government. Corporations. Once it became obvious people were coming here, we made plans. We had a pipeline brought in, totally off the books. We built a power plant. And we had no worries about planes flying over since we are surrounded by installations.

“We never tricked anyone or lied to anyone… not until I made the one mistake and tried to pass Cat Ivie off as myself for you. That was dumb. Mea Culpa. Anyway, as I said, and as often happens, the word about a gold find got out and people started showing up. Innovative, creative people. Folks looking for a new start. Lost souls and hurt hearts and the huddled masses yearning to breathe free, as they say. The new colonials with an old Puritan ethic. People with crippled hands like Carlo Rocca, but good intentions and a deep longing for substance. People like Carol and Leon and Kate Laird’s family. I called in friends who I knew wanted something more out of life. Old bandmates. Business partners. This town sprang up organically, Ken, although Copeland and I made whatever arrangements needed to be made to help folks out. Not a crime, as far as we see it.

“But that’s not really the point, Ken,” Lew said. “I told you all of this because I feel sorry for you, and what you’re going to have to go through from here on out. The fundamental premise of Nowhere was that we’re all people who just want to be left alone to be happy and live our lives. And now, you can see why. You’re a perfect example of why we tried to keep this place insulated from the world.”

“I—”

“Kate’s gone, Ken,” Lew said. “She’s gone and she’s done with you.”

“I can get her back,” Ken said. “We can talk it out. I can apologize.”

“Maybe. Someday. But not soon. And maybe never, too. And even if Nowhere survived this, which it won’t, you will never be accepted here. Not unless Kate accepts you, and I don’t see that happening. Not for… as the song says… a long, long time.”

“I can stop it,” Ken said. “I can stop the article.”

“It’s too late for that,” Lew said.

“It’s not too late! I can stop it!”

***

I left John Lee behind me and ran back to the basement, chest heaving, screaming Kate’s name. I had to rest for a minute when I got to the wine cellar, but then I was off again, flying through the house and then out through the gate.

Kate was gone. I searched everywhere for her. Abe’s taxi was nowhere to be found at the service entrance. The storm was whipping up strong and dark and the windblown sand stung my face. A rebuke. Raindrops were just starting to fall, stinging too, as I ran to the Packard. On the seat was the packet I know I should have opened earlier. The one from Thompson at LIFE. And I knew what it said now too. The same things that John Lee had just told me.

I ripped it open and pulled out the contents. And there it was, a dossier on Dick Hager.

Dick Hager – real name: Lewellyn Bonaventure.

If I’d read it when Kate had first handed it to me when she picked it up off his porch, he’d have known. I wouldn’t have made things worse. I could have backed out of all of it, maybe.

I started the car, jammed it into gear, and sped back to town. White-knuckled. Flooded with panic.

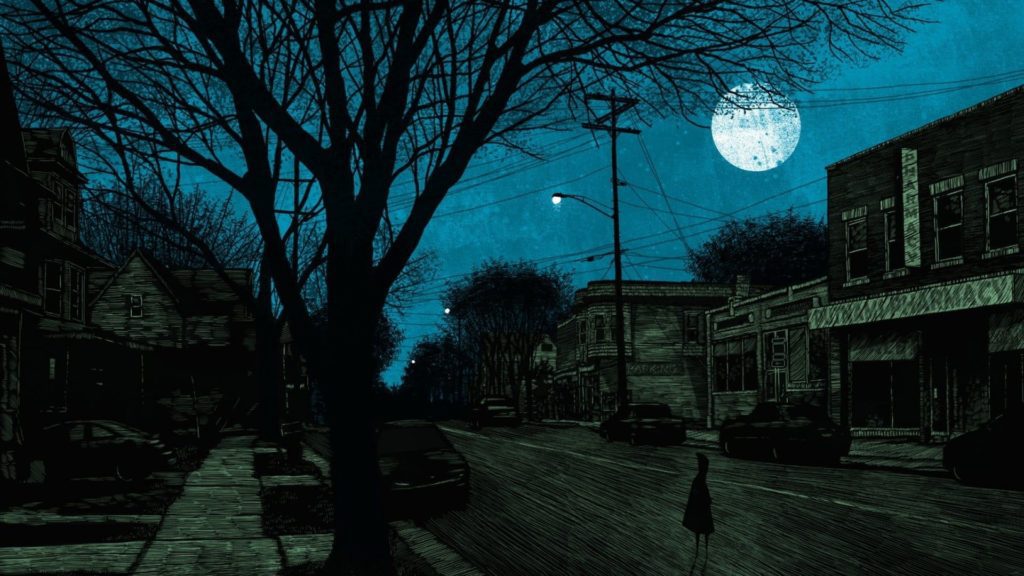

I drove for hours around a darkened town hoping to find Kate. I went everywhere looking for her. The Brick was dark, and it was that way everywhere I went. All the businesses and the lights in the Bistro District were black like the town had closed down for the storm. Kate’s house was dark too, and no one answered when I pounded on the door. Finally, I committed another crime and kicked the door off the hinges. The Laird house was empty, just like Bonaventure’s house when I first saw it. No furniture. Nothing. Even the art on the walls was gone.

I screamed. The same scream that Cain must have screamed when sent out to walk to and fro throughout the world alone.

I had the spare gas in the Packard, so I made the decision. I pointed the car northwest and out of town. I didn’t know the way, but I knew Albuquerque was northwest, somewhere, and I knew about where I could skate the mountains through the low hills around where Abe and I had refueled when I first came to Nowhere.

The road ended a half-hour out of town and the storm really hit then, and I was driving by feel more than by sight. By dumb luck and a trickle of misty memory, I found the overlook where Abe had his fuel storage. The tarp was there, but the fuel was all gone. Like it had all been a dream. I turned back to look at Nowhere and there was nothing there. Dark and obscured by the storm, and it was like it never existed at all.

The way out was straight north from there, from all I could remember. At some point, some hours due north I knew I just had to hit Route 66, then west to the city. I drove slowly because there was no road at all, dodging cactus and rocks jutting from the earth like teeth. I could only see a few feet in front of the car. The parched and sandy desert had turned to mud and torrent, a hell, and after some number of hours that I couldn’t count, I stopped in the deluge to pour in the last of the gasoline I had in the metal cans. Then onward again, like a lost calf or a soul being consumed by the storm. It was another slow, torturous hour—almost a foot at a time—before the Packard finally slipped in the mud for good and hit rock. Tires shredded, the car was stuck and there was no moving it.

I was on foot.

Soaked through, my feet slipped in the mud. I cut my hands falling, and several times went into the cactus. I tore my pants and shirt and my hair was matted with rain and mud and some blood. Eyes closed tight against the storm, but still I walked on, not knowing if I was even going north anymore and no stars or moon or other means to know.

My mind began floating and I lost any sense of reality, and when I peeked through slitted eyes, ghostly hands reaching out before me in the blinding storm. Every few minutes I’d fall again, crashing hard to the ground or spilling forward onto my knees, chest burying into the mud, rock, or river of water. And then I had to stop. On a small rise, not dry but not underwater. I couldn’t go anymore. I crouched down, hands clutching my knees, sat in the mud and waited. A purgatory or the waiting room for it.

I might have fallen asleep out of sheer exhaustion, but when I awoke the storm was gone. The night was black and cold in the damp air and the coyotes were close and the clouds had moved on and I could look up into God’s massive night sky and see stars. I read the stars using old skills, long unused, and figured out what way was north. Walking onward, finally coming across a highway, unlit and ghostly abandoned, running east/west, and I reckoned it had to be Route 66. I turned west and walked.

Not more than twenty minutes after finding the highway, I was picked up by a Good Samaritan who asked no questions and took me to a roadside diner. Coffee clutched in bleeding hands, a piece of pecan pie, then I cleaned up the best I could in the restroom and then called New York City collect from a payphone, asking for Edward Kramer Thompson at LIFE Magazine.

***

On that long-distance phone call, which cost LIFE a pretty penny, Thompson refused to cancel the article. Flat-out refused. Ken felt a new rage boil up in him, something born of some new chemistry churning within himself. The disappointment, fear, self-loathing, and inestimable loss that he’d bottled up during the whole harrowing trek from Nowhere to that roadside diner burst forth like a geyser over the phone line.

“I’ll tell you what you sonofabitch!” Ken shouted, “You’ll cancel that article, or I’ll throw your ass off the roof of that building.”

“Calm down, Ken. I’m not canceling the article. You can threaten me all you want. We already have it typeset. I did it myself. Besides, no one has read it but me. It can’t have leaked from here.”

“It’s all false, you bastard! And it did leak! The story is wrong! None of it is true. I got it all wrong, and if you publish it, you’ll open yourself up to a dozen lawsuits, not to mention one from me!”

“The lawyers have already vetted it. Nothing defamatory in it, even if it is wrong,” Thompson said. “You’re being emotional over some dame.”

“You said no one ever read it!”

“The lawyers have an attorney-client privilege. If they leaked it, they’d be disbarred and might go to jail. Still, they didn’t read the whole article, just a few selected short passages that could have been problematic but didn’t tell them anything. They weren’t a problem. Believe me, Ken. No one has read that article but me.”

“Stop the process,” Ken said. “I’m getting on an airplane in two hours, and I’ll straighten this right out or I’m dragging you up to the roof to make my point.”

***

Ken called for a cab to come get him from Albuquerque, hoping his cabbie would be Abe Mendoza. It was a forty-five-minute wait for the taxi, and when it arrived the cabbie was an old white man who claimed to never have heard of Abe Mendoza. Ken had a general idea where Abe’s house was, but when he finally found it, the house was empty. It looked like no one lived there.

Ken stopped by a telegraph office at the train station and sent a tersely worded cease-and-desist order to Thompson. It wouldn’t stop Thompson from publishing, but it would help with a lawsuit if he decided to pursue that option. Halberson operated as a private contractor—a stringer, in the business—and still hadn’t been paid for the article, so legally and technically the article still belonged to him. In court, LIFE could argue that since they were paying Ken’s expenses, any work he produced while on assignment from them, belonged to them, but there was no guarantee they’d be able to sway a jury. Especially if it became known that Halberson was trying to stop LIFE from publishing an article they knew to be false, and now with the receipt from the telegram he had proof of that if he needed it.

And those were the best cards Ken held. He needed to convince Thompson that publishing the article would be worse for the magazine than the interest they’d get from it.

Halberson placed one other call from the train station. He used the phone book and hired a man to go look for the Packard, giving him general directions and distances and promised an ample reward if the car could be recovered. If not, Halberson would pay the man his fee from his own pocket. He didn’t know who owned the Packard officially, since Thompson had denied ever seeing a bill, but he’d grown to like the car and hoped then that it could be found and repaired.

It never was.

After that call, Ken finally had the cabbie take him to the airport. He boarded a flight a few hours later. He slept on the plane, and after a connecting flight in Kansas City, landed at LaGuardia before midnight. It had been one full day (plus a few hours) since he’d left Nowhere.

***

Thompson was still at work at 1 Rockefeller Center when Ken arrived, and the editor called down to the doorman to let Halberson come up. Ken felt a stab of indescribable sadness when the elevator swooshed open on his floor, a brief micro-second flash memory of the elevator swooshing open to the ballroom at

Bix’s… another heart stab. Another death. He sighed deeply as he walked past the desks and side offices leading to Thompson’s office. Something about being back in the office made him think that maybe Nowhere had never happened. That’d he’d never seen that paradise in Spring, never held that silken hand or looked into those cornflower blue eyes, never watched the Sandlot Boys play ball, nor stood with her on the terrace and upon the rooftop above the ballroom at the Downtowner kissing her on the most beautiful evening that had ever been.

It was all a dream.

Except for the scratches and wounds on his hands and face said it wasn’t a dream. Testaments to his fall. The people on the plane looked at him askance, wondering what kind of lowlife he must be. And when he entered Edward Kramer Thompson’s office, Thompson let him know about it.

“Dammit, Halberson! Did you get dragged behind a palomino all across the Ponderosa?”

“My appearance,” Ken said, “should indicate that I’m not to be messed with at the moment. I’m in the mood to have my way and I shall have it.”

“A drink?” Thompson said as he moved to the bar in his office. He added two large chunks of ice, then poured scotch all the way to the rim, then handed the drink to Ken.

“Yeah,” Ken finally answered. “I’d like a drink.”

“Are you okay?” Thompson asked.

Ken shook his head. “I’m not. And I may never be ok again.”

“This from the guy wounded in France in the war, then blown apart in another war? The guy who has bedded Liz Taylor and Rita Hayworth?”

“Lay off of that stuff,” Ken said. He didn’t shout it. Wasn’t mad. His tone was one of resignation as if he just didn’t want to hear anything about himself ever again.

“Are we going to talk about it?” Thompson said.

“Not now. Maybe someday. I’m shredded Ed, and I don’t know if there’s any way to stop what’s happening. But you can’t publish that article. Not now. Not ever.”

“And I don’t get a why? At least a story? A lie? Anything?”

Ken swallowed the drink, rose, and then poured himself another. He slammed that one too. “I will tell you this, Ed. And I tell you this as a friend. If you publish that article, or if anyone else reads it, I’ll sue you and I’ll win. But I’ll do more than that. I’ll go on a speaking tour, and I’ll tell every media outlet in this country and around the world that LIFE Magazine published a story that they knew was full of lies. And I’ll tell the truth. And I’ll lie too if I have to, to make it stick.”

Thompson handed his glass to Ken who filled both glasses, this time with no ice, returning one to Thompson. “Calm down. I was already convinced by our talk on the phone, so don’t think these latest threats swayed me. I’ve faced down angry journalists who aren’t as broken down and crippled as you are, and I used to be a stringer too, so I know the score. I’ve known you for a lot of years and I still think your best writing days are before you, so I’m not going to ruin our relationship over this thing. But, my friend, you have to come back here someday and tell me the whole story. For my own sanity and… curiosity, I guess. I just need to know. If this were in a book, no one would believe it.”

“Maybe. Thank you, Ed. If I can, I will.”

“Take some time off, Ken. Go. Exorcise your demons. I suppose this all has something to do with a dame, and if it does, I hope you… well… I hope things work out.”

“Thanks.”

Thompson sipped scotch, then placed the glass on his desk. “We’re going to pay you anyway, Ken. Something tells me you’ll need it. I can tell Luce that you’re working on something else. Besides, we have a replacement story for the July 26th edition, the one wherein your epic story was scheduled to run. It seems Joseph N. Welch, Army Counsel in the McCarthy hearings, has written us a dandy and we’re going to run it on the cover instead of yours if nothing else pops up. He’s the fellow who told old Joe McCarthy “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” You probably missed that. Got a damned ovation. He’s a darling in the media right now, so his article will do well. Not as good as yours would have, but it’ll make Luce happy, and he won’t ask questions.

***

I was feeling low. Like garbage. The whole affair was on me now, weighing on me like Judas and his thirty pieces. I spent another day in Manhattan, clearing up business. Sent a telegram, hoping to find Abe Mendoza. Told him to tell John Lee or Copeland, anyone he could reach, not to worry. The article was squashed.

The next day I packed up the Samsonite with my notes, packed my clothes, then I was back on an airplane and headed for Albuquerque.

I bought another automobile from Galles Motor Company. Paid cash from the money Thompson gave me. A ’52 Packard this time. Brown with a light tan top. I bought four gas cans and had them filled at a filling station while I looked at and marked up a map. I could backtrack to the diner where I’d been taken by the Good Samaritan, then east a bit before turning south. I wasn’t sure I’d be able to find Nowhere, but I had a general idea where to look. I was hopeful.

Hopeful doesn’t buy you anything. I never found the place. Never found the overlook where Abe and I saw Nowhere for the first time. I drove around the desert for two days and… there’s no explaining it. Nothing looked familiar. I was turned around. I was sober. I was heartsick. I’d looked at the mountains from Nowhere a thousand times, but it didn’t help me when I was on the ground. Searching. I couldn’t find a clue as to where Nowhere was.

My gas situation was getting critical, so I had to call off the search and I headed back to Albuquerque. I spent two days looking for Abe Mendoza, even going to the cab company, to no avail. Everyone said they never heard of the guy.

I called in favors from Thompson and headed east again, this time driving all the way to Lubbock, Texas. Just outside of Lubbock, west of the town was Reese Airfield. Reese Air Force Base was the home of the 3500th Pilot Training Wing. Thompson knew the base commander and through him I was able to make contact with a pilot training officer who told me that there was a place out to the west, about where I’d explained, that had just been taken off the no-fly zones. Just in the past week. He agreed to get a private plane and fly me out to that area, and for the first time, I really felt like I might make it home.

Home.

Isn’t that strange?

***

Halberson’s notes are fragmentary from here on in. Bits of paper and hand-drawn maps. One long typewritten segment from when he finally found Nowhere, but the rest is bits and pieces.

Overflying the area, Ken looked down and saw a scar across the face of the earth. A wound on God’s creation where something important once had been. They found the airfield, abandoned, its runway raked away to obscure it, but still visible from fifteen hundred feet, though already starting to be reclaimed by the desert. But there was nothing else. Where the power plant should have been, there was nothing. Where John Lee’s mansion was… nothing. Ken saw the road he’d known as Northwest, also scraped away, just remnants of a track on the desert floor, but it ran to the big scar rather than to any town. There were no buildings, no palm trees, no Downtowner towering over the Brigadoon of New Mexico. It was all gone.

Back to Albuquerque, more cans of gas, and then the drive to the big scar. This time Ken had a map and a compass and knew where he was going.

The scar was just that. Kate was right, the whole place had been bulldozed. Scraped off the face of the earth. Ken collapsed and wept, hands raking through the sand and dirt. His heart was cratered in his chest, the deep sinking feeling of a death sentence was on him. He walked for an hour, tears clouding his eyes, searching for any sign that would tell him of something he’d once known and loved.

Here, he found a small brass tray and he knew it immediately. A cigarette tray from the bar at The Brick. He pocketed it and kept walking. There, reflecting in the sunlight, was a fragment of faceted crystal, a remnant of the glorious chandeliers from Bix’s ballroom atop the Downtowner. Now it was a keychain from the Dipsy Doodle. And then he found it. The thing that put a dagger into what was left of his heart.

The sand had buried it, mostly, but his eye caught the white of it and the red stitching. A groan escaped from so deep inside of him that he thought it had come from the center of the earth. A groan of despair and loss like Napoleon as he watched Moscow burned by its inhabitants rather than give him his victory.

He scratched at the earth, freeing the object from its desert grave. And there was the name written in the master’s hand…

Mickey Mantle

Ken sank to the ground in sobs, pounding the ground with the hand that clutched the ball.

“Why? Why would you do this? Why destroy it all?” he screamed.

Then, it occurred to him. It was him. He’d done it. But he hadn’t destroyed anything. Nowhere was still out there. Not rebuilt yet, but it would be. Nowhere would continue. They’d excised the one cancer in the otherwise perfect body politic. They’d removed Ken Halberson.

Somewhere Kate Laird was out there too. And John Lee and Copeland, Carlo Rocca, and Verne Powell. Leon McClain and Carol Cole, too. The Sandlot Boys would play again, but not with Ken Halberson watching on.

It all dawned on him like a baptism. Like water overflowing him as he knelt in the sands of what had been, to him, the greatest civilization.

They’ll rebuild it.

They probably already are.

“I’ll find it,” he said. “I’ll find it no matter what I have to do.”

Doubtful. My research says that Ken Halberson was in Cuba in 1961 and won the Pulitzer Prize. And he died in Albuquerque in 1974 in a car wreck. Probably still searching for Nowhere.

That’s what I knew when I got to the end of Ken Halberson’s notes. I emptied out the Samsonite and that’s all there was. End of the story.

But was it?

Leave a Reply