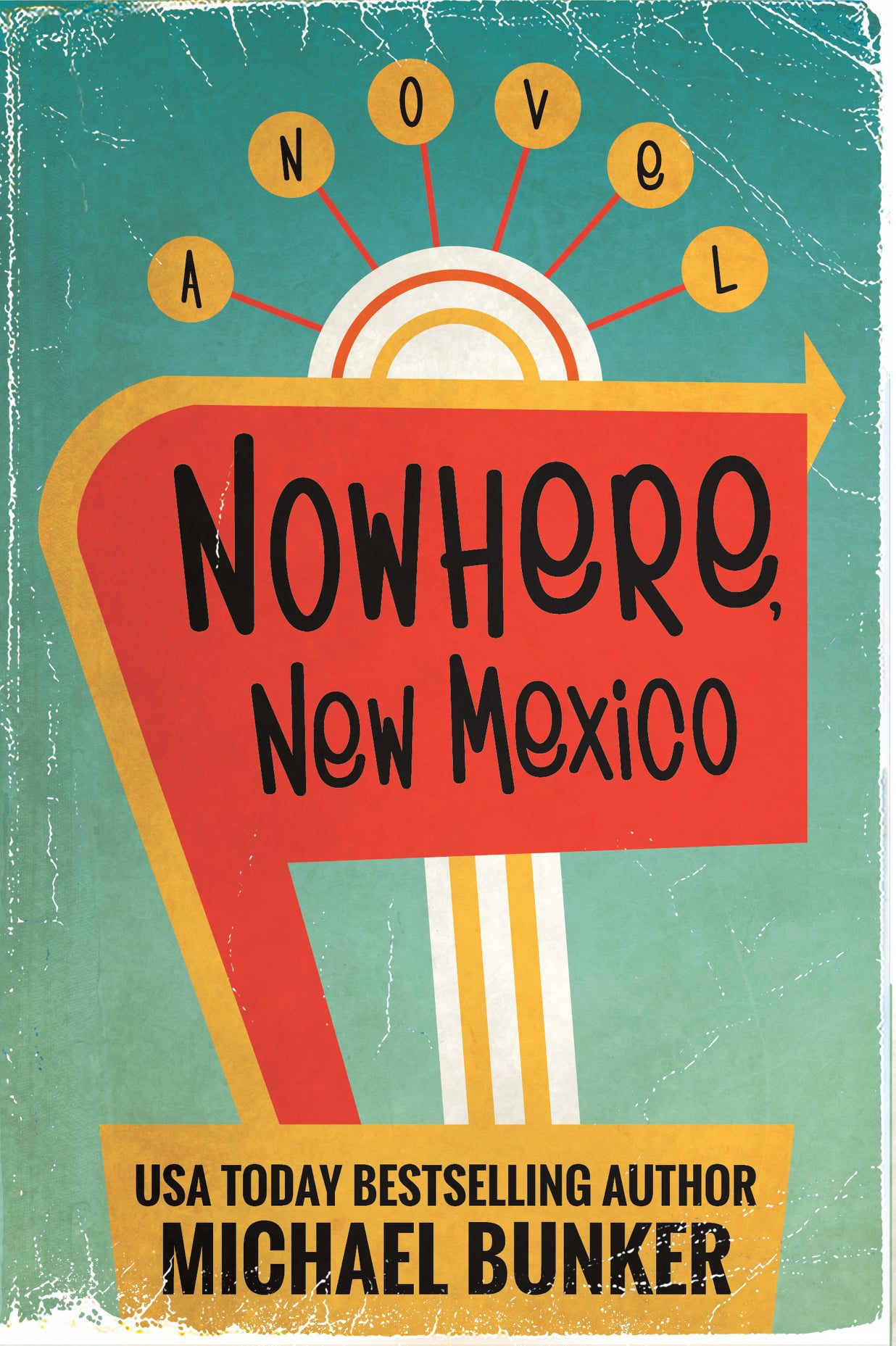

Ken Halberson

All Things Bright and Shiny.

“Without the gold, no one would be here. We wouldn’t, and you wouldn’t either.”

That was it. That was the hook. The line that was supposed to snare them into reading the whole article. First lines are critical in writing, the experts and editors say. Well, I had a doozy, because it was what Leon McCain said to me on my first full day in Nowhere, New Mexico.

And there was another quote to use. From when I’d confronted Copeland and asked him to set up a meeting between me and Lew Bonaventure. Copeland tried to assure me. He said, “Ken, there is so much gold you can’t imagine it all. Miles and miles of it. Enough to buy a country.” And now I knew it was all a lie. The town was built on a foundation of fool’s gold. Made up, pretend, non-existent fool’s gold.

I didn’t tell anyone what I knew. That night after discovering the truth at Dick Hager’s apartment, I went home angry. The next morning at 4 a.m. I brewed coffee and I started writing my article. I titled it All Things Bright and Shiny. For the next week I couldn’t let on that I knew it was all a fraud, so I had to pretend with Kate and with everyone else that nothing was wrong, that I hadn’t been lied to, and that everything was ok with me, even though it wasn’t.

I kept it all straight, though. I was two people now. One who truly and deeply loved Nowhere and loved Kate and could enjoy a day hanging out together, walking in the park, going to our favorite joints. That one could pretend he wasn’t in a manufactured dream. And there was the other guy, the realist. The one who’d seen the Great and Powerful Oz behind the curtain. That guy was alone, writing angry in the dark. Swinging a sledgehammer at all of it.

Here’s how I had it figured:

Copeland was Lew Bonaventure, and there was no real Lew Bonaventure. Copeland made him up. That was the skinny of it. Maryweather Copeland started Nowhere because he didn’t like the world he lived in (the actual, real, sometimes ugly, inconvenient, difficult world,) and wanted to create a Utopia where people lived without government or written rules or insurance or… I don’t know… the stark realities of modern living. The ex-G-man wanted a town with all the positives of modern urban life and none of the negatives. He wanted a fantasy, and he was willing to buy it at any cost and deceive people in order to make it come true. In order to hoodwink people into buying into the fantasy, first, he recruited some other unhappy rich people. People like Dick Hager (now calling himself John Lee Danner.) To my thinking, Copeland and Hager concocted the “we found gold” myth to tease people into searching for the town. People like me. Searchers who liked mysteries. Not people who were particularly looking to become gold miners per se, those were the losers in any gold rush, but people who knew instinctively that a gold rush town would be flush with economic opportunities. It was really a brilliant plan because only a certain type of people would be attracted to that bait: The people who were creative, intelligent, and motivated enough to 1. Find the place, 2. Get there, and 3. Make a go of living there. These were the people Copeland and Hager wanted. The narrative was self-regulating. By definition, colonists are industrious, optimistic, and hard-working folks. Look at how they started America. Same theme. Same work ethic. Second, to sweeten the opportunity, Copeland opened a “bank” (I doubted it was a legally operating, federally insured bank, but who knows?) and began giving low-interest loans. He didn’t really care if he was paid back (even though it seems like he was) because he wasn’t investing for monetary gain. Profit wasn’t even a consideration. He was investing in infrastructure and ‘happiness’ gains. If Leon McCain and Carol Cole built a hotel, well, now there would be a nice, modern hotel in Nowhere. If Carlo Rocca built a sweet shop, now your perfect little town has a sweet shop. So, it wasn’t the money Copeland was looking for, he had enough of that. He was looking to buy a lifestyle. Heaven on earth. Thus, the myth of the ‘Perfect Town.’ Third, Copeland had contacts from his time in government who served in military and civilian intelligence and law enforcement. Using those resources, he found a location that had unique qualities. It was very difficult to get to and was surrounded on all sides by off-limits and top-secret facilities. One that was easy to hide. He didn’t come to this land because he thought it was rich in gold—that was the charade—he came because it was perfectly situated to be almost self-hiding. Some people might say that my theory is an ex-post-facto fallacious interpretation but just do the math. If you had to find a place that was nestled between top-secret lands, was hard to find and difficult to get to, and one where you could tightly control how much information the outside world had about the town, you’d put a huge X right where Nowhere, New Mexico is. Was that by happy accident? Did all that happen and there also just happened to be gold here? Gold, by the way, no one has seen, and that hasn’t even blipped on the government’s screen? I wasn’t buying it.

I’m guessing Copeland paid a pretty sum—probably in bribes, donations, or contributions—to have his little town plot considered a no-fly zone. It wouldn’t have been hard to do, no skin off anyone’s nose, since most of the bases and airfields, and secret facilities in the area during and just after the war were already no-fly zones. The rest was just money and time.

There are the things I believed were true, but I couldn’t write all of that in my article. Nope. Get one supposition wrong and I’d be wide open for a defamation lawsuit. I had to come at it slant, as they say. Insinuate, but never say. I couldn’t say “Copeland is Bonaventure.” But I could say, “I think this, and this is purely my opinion, that Copeland is Lew Bonaventure.” I could say, “I suspect…”. I could say things like, “Isn’t it odd…,” or “So-and-so said… but how would we know?” I could wink and nod, report direct conversations, no worries on that, and I’d kept careful notes. I could surely say I’d been lied to, and I could prove it. And I could say, “if they lied about Bonaventure, what else are they lying about?” I had to be careful, sure enough, but I would make it known what I thought. I knew that my entire piece was founded on the proposition that Bonaventure didn’t exist and that I believed that Copeland was Bonaventure. That part I felt was pretty solid.

Why would Copeland and Hager try to pass off Cat Ivie to me as Bonaventure if the real Lew Bonaventure existed? That’s the dagger, right there.

Then there was the pretend Bonaventure’s empty, almost movie façade house. Like something on a Hollywood backlot. Sure, technically I could get charged with trespassing for going over the fence, but by whom? No one lived there, and as far as I knew, there wasn’t even a policeman or sheriff in Nowhere to arrest me. I never saw any law enforcement in Nowhere. That would scare the squares reading LIFE. But the empty Bonaventure house was a nail in the coffin of the Nowhere myth, so it was staying in the story.

Then there was the secret airfield and the expensive transport of goods in the middle of the night to keep the town supplied. Not illegal, certainly, but fishy as hell. Think about it. It was like the Berlin Airlift every single night, and you don’t think America would love to read about something like that? All because a couple of eccentric millionaires didn’t want a real highway coming here, with a real gas station along the way, bringing real people with all their flaws to

Nowhere.

I didn’t even need to mention things like state and local taxes, (which I assumed were not being paid,) public education, (which I assumed didn’t exist,) and hospital and emergency care, (which… who knows?) Did no one get injured or have heart attacks in Nowhere? The squares would be rioting.

These were the things I didn’t mention because I knew the readers, once they were suspicious enough, would do the rest of that mental exercise on their own.

The story almost wrote itself.

Was I bitter and disappointed? You bet I was.

And then there was Kate. What to do about Kate? In my anger, I convinced myself that Kate would see it as I did once she knew that the whole thing was a house of cards. A Potemkin Village. Just like Copeland’s Operation Fortitude before D-Day where they built entire divisions of an army that didn’t exist (You bet I was going to mention that in the article.) Copeland was trained in large-scale sleight of hand operations. He’d fooled Hitler. Kate would be mad at first, then she’d come around. She’d see that I was after the truth. She’d understand that she, too, had been lied to. She’d love me for telling the truth and for not joining in with the lie. Then she’d come with me out of Nowhere and we could start our lives together.

Sure, I was angry. I hated the dishonesty, and my emotion was an impediment. I knew from experience that being emotional makes the job harder. During that week when I was writing the article, my mental state was unsteady and tempestuous. A knife’s edge. I was on a roller coaster. At one moment I’d feel elation and satisfaction, almost high, at having broken the spell of the town. I felt like I’d uncovered a spy ring or a long confidence game that had taken years to set up. And if I’m honest a part of me—a darker part—wanted to expose something that was considered ‘perfect.’ To mar it somehow. Maybe we all feel that way sometimes. I don’t like to think about that motivation. Then, almost in the next instant, I’d feel down, depressed, and afraid, like my darker angels were trying to turn my beautiful memories of Nowhere—like the night of the Spring Celebratory Ball or sitting on the picnic blanket with Kate watching the Sandlot Boys run the bases—into something black and sinister, and my mind and heart together were rejecting the conflict. I knew I’d have to throw it all out, all the feelings, become dispassionate, and just keep writing.

I was afraid that maybe I’d missed something. Blinded by passion. Lost in a tempest. Maybe Kate wouldn’t see it my way and I’d lose her forever. One minute I was dreaming of accepting a Pulitzer with Kate on my arm, and the next I was shunned and rejected for destroying something that other people loved. Dying alone and sad.

I steeled myself and just wrote. Ten thousand words that took a sledgehammer and a wrecking ball to Nowhere, New Mexico.

Two days after I finished the article, I saw Abe Mendoza sitting in the diner of the Vacation Motor Inn, the place where it had all started for me. The man who brought me here. I had the manuscript for my article sealed in an envelope and ready to be mailed to LIFE. I chatted with Abe and didn’t let on what I was doing. He had no reason to be suspicious, so he took the envelope and we shook hands and hugged and Abe headed back to Albuquerque. In a week, I guessed, no more, Edward Kramer Thompson would have the article, would read it, edit it, and he’d start scheduling its release. All-in-all it would take some time. Depending on how Thompson felt about the story, he might make it a cover story, in which case the article wouldn’t come out for months, maybe even six months. If he didn’t think that much of it, and if he needed filler for an issue, it could be out sooner, but we were still talking a month or two.

I thought I had time. I could explain to Kate and work on her. Slowly. Bit by bit. I had time, didn’t I?

I never dreamed the wheels would come off so fast.

***

I’m reading Ken Halberson’s notes again and my heart pounds, like when I’d watch a thriller movie or when I expected something bad to happen. The clues of a disaster brewing began appearing sooner than Ken imagined. The first sign that something was amiss was, appropriately enough, an actual sign. Driving up Southwest Drive, Halberson saw a FOR SALE sign in front of a house, like a dark harbinger or an evil omen. He’d never seen a FOR SALE sign in front of a house in Nowhere before. That was one of those things that Ken never thought about until it smacked him in the face all at once. Sure, he assumed that people bought houses. Clearly. That would make perfect sense. And people upgraded homes at some point. Maybe when a family moved to Nowhere, they had a two-bedroom house built, and now, five years later, they had more children and needed something bigger. New houses were being built, and if someone was moving to a new house, they had to sell their old one, right? So, it wasn’t strange to conceive of someone selling their house. What was strange was that Ken could not remember ever seeing a FOR SALE sign anywhere in the town.

But there one was.

And then there was another one on Mockingbird, FOR SALE BY OWNER, white and shiny with red print and standing out like an accusation. Maybe it was the next day that Ken saw it. Then later that day he saw the third one and a fourth. Then, even later on that same day, he saw a station wagon heading out of town, packed to the roof with household goods, kids jammed into the second-row seats like arrested captives, and gas cans strapped on the luggage rack with rope.

Ken felt like a horse kicked him in the heart.

That’s when people stopped talking and being friendly with Ken, and it coincided with Kate not seeing him. And it’s not like she was refusing to see him. No. She was just busy. He’d knock on her door and her parents, cold and aloof now where they’d been friendly before, would tell him she was washing her hair, or she was busy doing something and couldn’t come to the door. He’d leave her a note:

Kate, Please talk to me. I can explain. Ken.

Before, he’d been treated hospitably, even like a celebrity. Now at his favorite restaurants and bars, Ken got the cold shoulder. Nothing overtly hostile or confrontational, but not the usual friendly service. Perhaps his little brass tray at The Brick was empty and never filled with cigarettes. He had to wait and call someone over to get his drink refilled. Nobody said hi. There was no pleasant chitchat with the staff. Leon and Carol didn’t come over to talk to him.

A few days later, some places stopped seating him altogether. At Papa Ricci’s, his favorite late-night place for wine and cigars, they would tell him they didn’t have any tables and that he needed reservations, even though the place was almost empty. He couldn’t get a seat at Las Lunas either. And people crossed the street rather than have to walk by him and maybe say hello.

He got a little worried that he might get run out of town, so on the day when he was turned away at Las Lunas, he stopped by the gas station and bought two gas cans and filled them with fuel. Just a precaution. The station attendant wasn’t surprised and seemed happy to see Ken apparently leaving town.

Ken tried again to get a message to Kate, but it wasn’t happening.

Then the exodus began in earnest. He spotted a veritable wagon train of vehicles, ten or twelve, packed full like it was The Grapes of Wrath and accompanied by the town’s gas truck, heading out of town.

The Sandlot Kids weren’t playing ball anymore, even though it was baseball season, and when he was lonely and decided to drive out to the Regal to see a movie at the drive-in, most of the other cars returned their speakers to the stand and left rather than watch the movie with Ken Halberson there.

All he could do as he sat alone in the Packard and as the movie played ghostly on the screen, was wonder how the story had gotten out. Thompson would not have leaked it, but, like the legend of the original Nowhere gold, the gist of his article had absconded from LIFE Magazine and it was in the wild. Everyone in Nowhere knew it, Ken could see it in their icy glares. Most likely it was a loose-lipped typist, or maybe another editor looking at the article, sizing up the amount of space it would take in the magazine, or a telephone operator on the switchboard at 1 Rockefeller Center who overheard a conversation and right there began a real-world version of the grapevine game. Thompson would have ordered copies of the article typed up, that was pretty common. In this case, he certainly would have put a code on the article equivalent to a TOP SECRET designation in the government realm. But secrets do escape. Doesn’t matter how. Somehow, someone at LIFE had called someone somewhere else and the story of the fake little town full of naïve and gullible idiots chasing gold had leaked. And once it got out, there was no stopping it. Any number of reasons existed as to why some resident or another of Nowhere would want to beat-feet before the article hit the newsstands. Pride, anger, fear of loss or ridicule, economic considerations, I mean property values would plummet because who would want to buy a house in a town founded on a long con by a rich dissembler? Ken hated to see it, but some people just run rather than face the truth.

Reading his notes almost seven decades later, I saw that Ken was a man torn. I try to understand him but sometimes it’s difficult.

***

I decided rather than wait around and be persona non grata in the town, I’d find a way to talk to Kate. Maybe, if I could convince her to leave with me, if I could convince her I was right and that the town was built on a lie, well… I don’t know what… maybe we could leave together. Go to Albuquerque. Elope. Get married and go somewhere else and wait for the article to come out in LIFE. I knew that if I could just talk to Kate, I could make her see reason.

What I was seeing every day now in Nowhere was breaking my heart. I never wanted to destroy the town. At least I don’t think I did. In my anger, I wanted to destroy the idea of the town. The bogus image of it as some perfect utopia that condemned the rest of the world by its mere existence. I wanted the myth to die, but not the town I’d come to love.

The next morning, I staked out her house. I waited up the street and smoked cigarettes and tried to work out the phrasing of my case; how I would convince her that I was right. It was early in the morning when I saw her leave and walk toward downtown. I got out of the Packard and ran after her.

“Kate! Kate!”

She acted like she didn’t hear me. Her back stiffened and she picked up her pace.

“Kate! Please! Just talk to me.”

She halted. She didn’t turn around, she just froze. I ran to catch up and when I did, she swiveled on her heel to face me.

Her face was stone as she glared at me. I didn’t say anything, because what I saw scared me.

“Meet me at your apartment at noon,” she said, almost in a whisper.

I sighed and then nodded. She didn’t want to be seen talking to me. She walked around me and was gone.

***

Kate was at Ken’s apartment precisely at noon. He let her in when she knocked, and she handed him a package that had been sitting on the porch. He took the package and tossed it on the table, offered her tea, but she turned it down with a wave. Instead, she removed her gloves and sat on the sofa.

“I want to be very clear with you, Ken, and I don’t want this to turn into some kind of fight. Some kind of shouting match. I’m going to try to be unemotional, so if you aren’t willing to listen, I’ll just get up and leave.”

“Unemotional? Kate? I love you! I have loved you since I met you, and I know I haven’t said it, but I do.”

“Leave all that aside,” Kate said coolly. “You cannot fathom what you’ve done. The damage you’ve done. What a fool you’ve been. And that you’ve done it with no consideration for me, my family, or of anyone else in this town—”

“Kate,” Ken said. “I only told the truth. I can prove it.”

“You can do no such thing because your entire premise is false. And you built on it a foundation of sand. Error upon error. And I don’t get why. I don’t understand what it is in you that would make you do such a thing!”

“Bonaventure doesn’t exist,” Ken said, spitting it out. “Copeland is Bonaventure like I told you. And there isn’t any gold! I have a government report I can show you that states that there’s been no unexpected or unexplained increase in the gold supply. None.”

Kate laughed, but it wasn’t a mirthful laugh. It was a laugh of anger and derision. Dripping with sadness and disgust. “Do you even hear yourself? Those two statements are incompatible, Ken! If Copeland is Bonaventure, (and he isn’t,) but if he is, then Bonaventure exists. But forget that for a moment because it’s stupid and false. Bonaventure does exist, and Copeland isn’t him. I know him, and you do too. And the gold is there, I’ve seen it! So, every word that comes out of your mouth from now on directly contradicts what I’ve already told you. You are not calling Copeland a liar, or Bonaventure either. You are calling ME a liar! And I won’t stand for it.”

“I’m supposed to just trust you and not what I’ve seen with my own eyes?”

“Yes, Ken. Yes, you are!”

Ken got up and walked to her. He kneeled and clasped her hands in his. “Kate, just listen to me. I can prove it to you. I’m not calling you a liar. I’m saying you’ve been deceived. I’m saying I can show you. I can prove it.”

“You can never prove it, Ken. All you can do is prove yourself to be a fool. But, ok. Prove it to me. And when you fail, as you certainly will, I want you to know that it is over between us. Finished. It will take time for God to show you whatever it is that is in you that has perverted your judgment so much that you can take this beautiful thing… this beautiful place… this beautiful us… and destroy it. If He ever does show you, then… I don’t know. I can’t wait around for that, so after what happens next, just know that it is over.”

“I love you, Kate.”

“I love you too, but it doesn’t matter. You’re deeply skewed, Ken. Something in you is broken. And I don’t know if you’ll ever be right again.”

“Just let me show you.”

“You’ll be showing yourself. But let’s do it and get it over with.”

***

I offered to drive Kate out to Bonaventure’s to show her the empty house, but she wouldn’t get in the car with me. She told me she’d meet me there in an hour, so I packed my things, placed all my notes into the Samsonite, and loaded all of it into the Packard. As soon as I showed Kate the truth, proved it to her, and as soon as she knew there was no gold and that Copeland was Bonaventure, we could just get in the car and leave Nowhere tonight. Head to Albuquerque. I packed the full gas cans into the trunk just in case Kate agreed to leave with me.

Out to the mansion, and I parked again in the trees at the service turn-off. The night was hostile, brooding, and a storm was blowing in. The wind whipped at me and clouds rolled in, darkening the sky. I don’t know how Kate would be arriving, but I’d wave her down when she did. Ten minutes later I saw the headlights and as the automobile rolled up, I recognized it. Abe Mendoza’s taxicab. Abe got out and shook my hand, but there was sadness on his face. Disappointment. As if someone he loved had died, or maybe I’d died.

“Amigo,” Abe said.

“Amigo,” I said.

“Leave the car running please, Abe,” Kate said. “I won’t be long.”

“Kate—,” I said.

She turned to me. “Let’s get this over.” I could tell she’d been crying in the cab on the way to the mansion. That, too, broke my heart. I never wanted to hurt her.

“Come with me,” I said. “We’ll go around back.”

Kate pulled her elbow out of my hand. “Why don’t we go in the front?”

“Technically, we’ll be trespassing. But no one lives here, so we probably could. Anyway, let’s go around back since I want you to discover it the same way I did.”

We walked rapidly along the fence line. “You silly, stupid man,” Kate said.

“You just wait,” I said. “Once you see this, you’ll understand.”

Kate didn’t speak again until I’d scaled the fence and then from the inside opened the service gate in the rear for her to enter.

“We could have walked right in the front door,” Kate said.

“Just… just come with me.”

I pulled out my flashlight and we walked to the back door. I shined the light in the windows and…

…my heart almost stopped.

The whole house was full of furniture.

Kate didn’t wait for me to accept what I was seeing. She pushed open the back door and walked in, flipping on the nearest light switch. Light flooded the room. She yanked off her gloves and slammed them on the table as she moved through to a large living area, turning on more lights as she walked.

The house was fully furnished. Where before the home was abandoned and empty, cold and dead save for the wall-hangings and art, now the house looked lived-in and comfortable. I was floored.

“Kate… I—”

“You what?” She went to an ornate, antique desk and opened a drawer. Rifling through it she removed a pile of papers and separated out some receipts, which she handed to me. “The place was empty for a week while the carpets were being cleaned and wood floors sanded and polished. The furniture was stored in shipping containers on the property brought in for the purpose. This is Bonaventure’s house.”

“I… I…,” I sputtered, mind reeling. “Listen. It’s a trick. The guy they call Bonaventure is a trombonist named Cat Ivie. I can show you!”

“The one mistake they made,” Kate said. “And the one, single, sole, only, damned solitary lie anyone in this town ever told you, Ken. That was a mistake. John Lee thought you were a good guy, and that if you could meet a Bonaventure, you’d let all of this foolishness go. He made a tactical mistake because he based his decision on his feelings for you. His affection for you. His opinion that you are a good man, and if you could be distracted, you’d just let things go. He has valid reasons for protecting his identity.”

I was looking around the house now, not believing what I was seeing. On the walls were pictures, paintings, and other fine art. Above a credenza, I saw a photograph and I moved closer. It was of Dick Hager and Copeland.

“See!” I shouted. “Copeland is Bonaventure! This house belongs to Copeland!”

“No, he isn’t! And no, it doesn’t!” Kate screamed at me. She was crying now. “I work for Bonaventure! I’m the one that is telling you!”

I threw open a door and a staircase descended into a dark basement. My mind was adrift, grasping. I knew that this was all staged. Had to be. Faked. There was no way it could be true. Somehow, they were still playing the game. “Come with me!” I shouted. We’ll find proof, I know it!”

Kate followed, but she was still trying to explain to me how wrong I was, but I wouldn’t listen. I knew what I knew.

“I’ll find it. Evidence,” I said. I was the one who was stone cold now. Matter of fact. I had to be right. I couldn’t be wrong. Searching the basement, looking for proof that Copeland owned this house, I could feel Kate behind me all the way. Distraught. She would pound on my back with her little fists, cursing me.

“Why won’t you just listen?” She cried.

At the far end of the basement was another door, so I marched over to it. “There is no gold, Kate,” I said. “It’s all a lie. I opened the door revealing another staircase going even deeper into the earth. I pulled the string on a light, then took the stairs two at a time and opened the door at the bottom. A wine cellar with racks and racks full of bottles of wine. Thousands of bottles. The whole wine cellar was a testament to time. Dust covered expensive investment wines. A part of my mind knew that this part couldn’t be a movie set. This wasn’t part of the fraud. This was real.

I felt the earth itself consuming me, like this deep under the desert maybe I could dig myself in and hide. Or maybe it was a grave. I stalked like a madman up and down the aisles of dusty wine bottles on racks, and at the back of the cellar was an old, ornate buffet cabinet. On top of it, leaning against the wall, a large portrait of Dick Hager and His Mighty Men. There they all were… Verne Powell, Carlo Rocca, even Cat Ivie, and the rest of the band. All smiles. The portrait was three feet across and probably four feet tall. I grabbed the painting and stared at it, turning toward Kate. I felt bolstered for a moment. I wanted to say, “Where is the gold, Kate? What are they hiding? Where is Bonaventure and why are there only pictures of Copeland and Dick Hager in this house?” But before I could say anything, I turned and saw that behind the picture… behind the buffet cabinet, was yet another door. The last hope that I’d be proven right. I placed the picture on the ground leaning it against a wine rack. Then I slid the buffet cabinet away from the wall, pivoting it so I could open the door.

“Ken, don’t,” Kate said. She was crying.

“I have to.”

“No, you don’t.” Tears poured down now, like a faucet or a river had broken open in her soul. “This once, you can listen to me and trust me. If you don’t, I’ll know everything I need to know about you right now. Right this instant, I’ll know.”

“We can’t build our love on a lie, Kate,” I said.

“Don’t open that door.”

“Tell me what I’ll find when I do.”

Kate sobbed. “Ken… I loved you. I… I still do. At least know that.” She broke down, crying into the back of her hand.

“Tell me,” I said.

“John Lee is Bonaventure. He’s also my boss. I’m his assistant.” She was speaking between sobs. “Everything you were ever told was true. Copeland was ‘Smith.’ Sent here in ’46 to investigate Bonaventure—John Lee—by the government, and… he and John Lee hit it off. They became… friends. They didn’t plan on starting a town. The word of the gold leaked out on its own. People started arriving, and John Lee and Copeland just helped them. Selflessly. Just like they did with you. Just like they did with Carlo Rocca, and Steve Durant, Carol and Leon and countless other people. And it turned into something beautiful—”

“Friends?”

“Yes!”

Ken scoffed. “Bonaventure, is Dick Hager, is John Lee Danner?”

“That’s his business, Ken. He has reasons that are better than you can dream of in your shallow, cynical world. But it’s his business, and if he wants to tell you, he will.”

“Where’s the gold, Kate?” I said.

Kate straightened up. Wiped her eyes with her sleeve. “It’s behind that door. The gold is right there, just a few feet away from you. More than you can conceive. And I’m asking you to trust me and not open it. To let this man keep his own secrets, secrets that are none of your business. Can’t something be private? Not the world’s business? Can’t people be free? I’m asking you to not need to know, Ken. Even if that’s counter to your nature. It’s just like the preacher said that first time we were in church together. You don’t need to know anything else. It’s the knowledge of good and evil again, but this time you’re the villain, Ken. If you can’t just let goodness exist, then you’re the villain. So just… don’t. Just walk away. Come with me. We’ll go upstairs and talk it out. We’ll try to work it out together. Give me that.”

I looked into her eyes, and then back at the door. And I truly, honestly, and completely believed that she was being deceived. That I could help her. Show her.

“I… I can’t.”

I watched her as her heart broke. Then I turned and opened the door.

Leave a Reply