Edward Kramer Thompson

America’s Pastime.

The weeks passed like the sweetest honey dripping from the comb. To change the metaphor, each day for Ken was his own private gold mine, a thick vein of the purest, most precious golden joy, bountifully new with each sunrise. He did not know if this that he felt was a love of the forever kind because his mother had warned him that so many other feelings, desires, and emotional artifices can masquerade as true love. Most people, she said, were deceived by fool’s gold—temporal, selfish loves—and because of this (she whispered the word because she found it too offensive to say out loud), divorce had gotten a foothold in society. People were marrying for a million artificial or transient loves and never seeking out the true kind.

This lesson from his mother had given him pause all of his life, and it was for this reason that he hadn’t rushed into marriage.

And what of now, this with Kate? Was there lust? Definitely, though as yet unpursued. The selfish desire for regular feminine companionship? Absolutely. A vain satisfaction with being appreciated? No doubt. When Kate looked at him, he felt entirely consumed by her, yet he remained and sought to be looked at by her again and to be consumed all over again. All of that. But there was something more here. Something deeply inexpressible inside himself. Ken began to recognize a need, heretofore unmet in his life, for completion. It wasn’t sex, it wasn’t companionship, it wasn’t wanting to be wanted, although it was also all of that. No, he recognized something else. A need that he’d been seeking unconsciously to fulfill all of his life. One that seemed to find satisfaction only in Kate. Being with her he felt whole, and this, he determined, must be akin to the love he’d been searching for as long as he could remember. Being separated from her, even for the night, he suffered want. A dull, throbbing lack. Something missing. But then she’d appear again, and all things were made new and whole again. His world awry spun rightly once more.

Ken noticed that it was taking a while to receive an answer from Edward Kramer Thompson, but he didn’t care. Life was sweet as spring passed and Easter swept by, and then there was the 30th birthday that he didn’t tell anyone about because he didn’t want any particular day or night to be about himself. Instead, Ken reveled in his growing relationship with Kate… and with Nowhere. While he still took copious notes and wrote in his journal nearly every day, he’d begun to lose the overwhelming curiosity that had caused him to look at everything and everyone around him cynically. Not that he stopped noticing idiosyncrasies, but he stopped attributing them immediately to some dark mystery that had an urgent need to be solved by him.

He would not have said so out loud, not even to himself, but he was beginning to feel at home in Nowhere, and with Kate.

The weather remained pleasant, though it did start to get warm during the days and there wasn’t much of a rainy season. However warm it got, the nights were cool and a nice breeze would sweep in from the mountains to the north and west and even when it was warm it was nice and not humid or muggy.

The time spent with Kate was precious to him. They didn’t see one another every day, but most evenings they would meet and stroll downtown or drive to The Brick to hang with John Lee, Leon, and Carol, or they would dress up and go to Leopold’s, or to Bix’s on a Saturday night. Sometimes they went for a burger to Bannock’s or the Dipsy Doodle. Most often, after dusk, they would walk over to the Bistro District and hang out at Las Lunas and dance, and wherever they ended up, depending on if there was live music that night, sometimes Kate would get onstage and sing, and Ken’s heart would soar like the first time he’d taken an airplane flight.

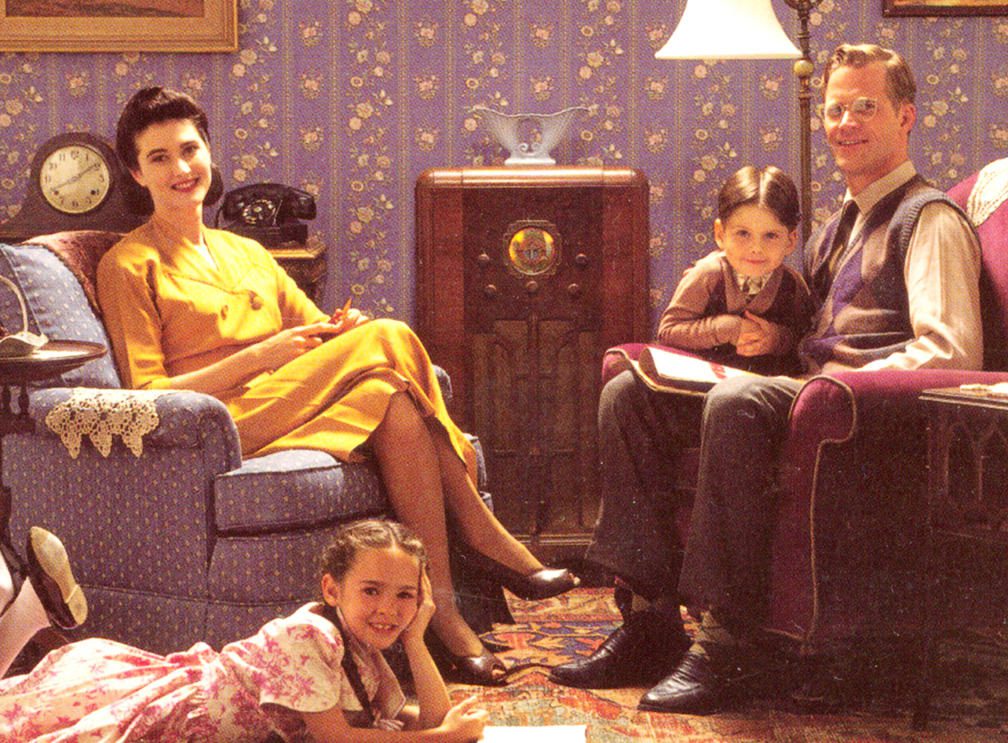

One Saturday in May they spent the day at Kate’s house with her parents, and after supper, Kate’s father studiously packed his pipe, lit it, then sat on the ottoman and tuned the wireless (it took quite some time) until he found news coming out of somewhere in the ether. There was no radio identification that Ken heard, so he didn’t know if this was some pirate station out of the Mexican borderlands, or maybe KOB out of Albuquerque (which could only be heard if the weather and atmospherics were right,) or it was one of the big flamethrower stations out of Dallas. Ken noted that it was the first actual “news” of the outside world (not counting the male gossip bandied about at Polly’s) that he’d heard since he first arrived in Nowhere. Nothing really earth-shattering. Nasser was made Premier in Egypt, and there appeared to be some sort of communist takeover in parts of Vietnam. After the news program music came on and they listened to songs by Doris Day, Nat King Cole, Jo Stafford, Rosemary Clooney, Louis Armstrong, and Perry Como. And Kitty Kallen too. It was the latter’s edition of It’s Been a Long, Long Time that Kate loved and emulated, and that song had become Kate’s and Ken’s song and whenever she’d see him, at his door or at hers, or if they’d meet at the grocery store, Kate invariably would say “Kiss me once, Mr. Halberson, it’s been a long, long time.” And after the music, there were a series of thirty-minute ‘shows’ that started with Jack Benny, and at some point, Gunsmoke came on.

After Gunsmoke, Ken and Kate excused themselves and walked to Papa Ricci’s and drank red wine and smoked cigars (Mama doesn’t like cigarettes, so Kate tried a cigar and liked it) and ate garlic bread, and despite the cigars and garlic, after Ken walked Kate back home, they kissed under the moon and promised to go to church together the next morning.

Ken floated home, bathed in the bright moonlight, and for the first time in his life, he thought specifically about marriage and having children and about maybe having a life with Kate in Nowhere. Kate was special. He saw no guile in her, no alternative motives. No agenda. She seemed perfectly at peace in the world and on Ken’s arm, and when she smiled at him he knew it was not a mechanism or a tool, but it was a legitimate, unconscious reflection of her happiness. She never pressured him using the usual feminine tactics he’d learned to spot because if she wanted something she just asked for it. Just like that first kiss on the roof of Bix’s that perfect spring night. This also seemed perfect, their relationship, and now he thought about why he was in Nowhere to begin with, and what was happening to him in the town.

It seemed apropos, then, that when he arrived home at his apartment, a package waited on his doorstep from Edward Kramer Thompson at LIFE Magazine.

***

The package was taped securely, and I noticed an almost imperceptibly thin red thread that had been placed under the tape, a message from Thompson that if the thread remained whole, my package had not been tampered with. It was a unique kind of thread, microscopically thin, that I remember from my past assignments, so I felt confident that no one in Nowhere (or anywhere else along the way) had opened the package to examine its contents, then resealed it. I opened the package and dumped the contents onto my rug.

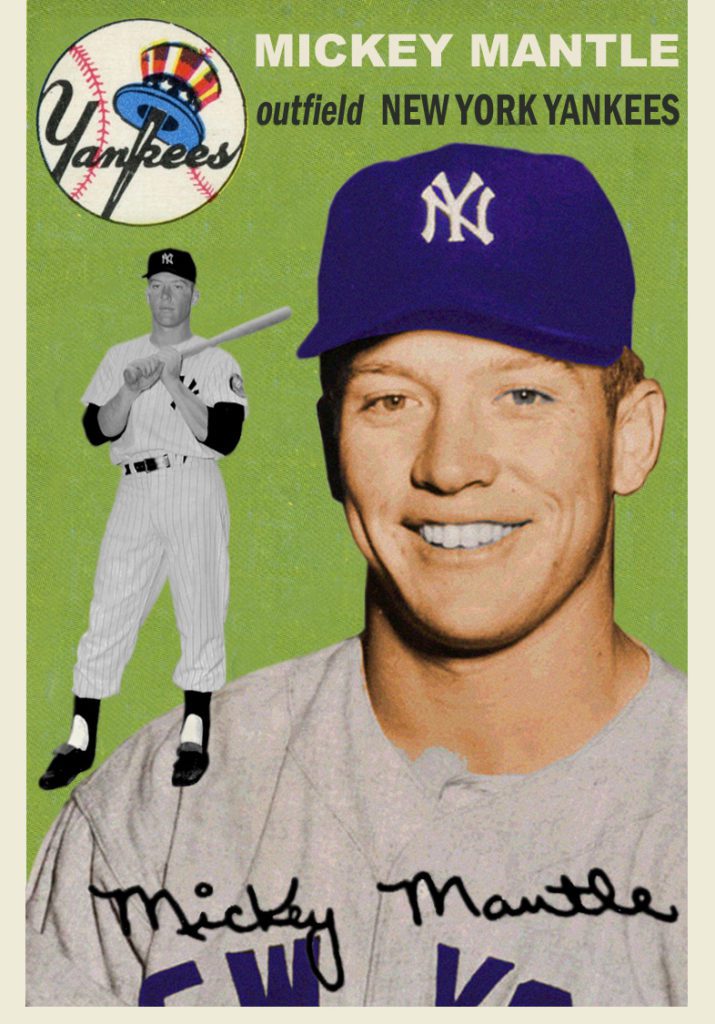

There were about fifteen baseball cards autographed by Mickey Mantle. I smiled as I examined the cards and saw that Thompson had gone to great care to make sure that Mickey himself had signed them. Perhaps, I thought, this is why the package had been so long in arriving and I realized I should have told the old man to expedite the Copeland information and take his time with the autographs if need be. In addition to the signed cards, there was a single, official, professional baseball, also signed by Mickey Mantle. For just a moment, the tiniest of a split second, I considered keeping the baseball for myself but decided that I could get one any time I wanted once this assignment was over and I return to New York, but it would mean the world to one of those boys at the sandlot.

When this assignment is over.

That thought hit like a ton of bricks. Did I really want this assignment to be over? Ever? And what about Kate? I knew down deep now that I wanted to marry her, even if I hadn’t said it in so many words to myself, but I also knew that it would be near impossible to get her to ever leave Nowhere. Kate and Nowhere were a package deal. I had no doubt about that.

If I stayed…

Would I really consider staying? Wasn’t I already considering it? If I stayed, I’d have to get a real job, I guess. Or maybe, I thought, I could write novels. Researching a non-fiction book in Nowhere would be a pain. I didn’t even know if Nowhere had a public library. And what about the thousands of pages of notes on Nowhere over in the closet in a suitcase. What of the story I was getting paid to write? Was I going to give up on it? I shook my head and realized I needed a drink.

I took the envelope off the floor and on it was the name written in Thompson’s own hand:

Maryweather Lansdale Copeland

I took the package, stepped out of the apartment, and solemnly breathed in the night air of Nowhere. Some part of me knew that I was reaching an inflection point. Maybe a precipice. A decision was in the offing, but I didn’t even know what my choices were. I wanted nothing but the perpetual bliss of my days and evenings with Kate in Nowhere, but a part of me that had once sat in a foreign hospital bed not knowing if I’d leave with my leg or my life knew that the truth I’d been sent to discover was still out there. I was on a truth mission, and those are serious business. I’d learned through my wounds not to give in to maudlin sentimentality or to the whims and caprices of emotion. When you have a job to do, you do it, and you let God sort out the results. I knew that if I didn’t follow through with my inquiries, I’d always regret it. I stepped off the stoop with the envelope tucked under my arm and walked back to Papa Ricci’s. The staff was surprised to see me back, but I was immediately taken to a booth in the back and as the waiter went to retrieve the red wine I ordered, I sat and pulled the contents from the envelope. Thompson never ceased to amaze me with his ability to pull strings and gather background information, and this file was no different. Someone with some level of government clearance had participated in assembling this dossier for me.

***

Maryweather Copeland was a bit of a cipher. Educated in the Ivy League at Princeton, one of those secret-handshake trust fund boys, it seems, but he’d left college after graduation and took a manual labor job in the oil fields outside of Tulsa before the war. Hard work by anyone’s standards, and he didn’t seem to have had any assistance from family money. When the war started, he enlisted in the army and—again, it appears, with no help from above—was selected by his merits to train and work in signals intelligence and then he graduated to field operations work. He’d moved to the OSS while still on active duty in the Army and had even worked behind enemy lines in Germany almost up until the very end of the war.

Copeland was a spook.

Copeland’s family was old money if you count old money as money made mostly in the last century. His grandfather got rich riding Carnegie’s coattails and then made his own pile on top of that in shipping. Copeland’s father followed his daddy and got super-rich on his own watch during prohibition, it wasn’t hard to figure how, although in the reports there is no direct connection made between father Copeland and organized crime. It seems that daddy Copeland’s ships were used to bring rum up from Cuba and whiskey from Central America, but somehow the elder Copeland had gotten rich breaking the law without sullying the family with Mafia ties, at least any that were obvious, unless that part had been scrubbed from the record.

When Copeland’s father died in the last year of the war, Maryweather became filthy rich by inheritance, however, there is no indication that he ever used the wealth for anything at all. Nothing in the files discussed his investments or told of him starting or investing in any businesses. Instead, he went to work for J. Edgar Hoover in the FBI as an entry-level agent in 1945, then he disappears from the record altogether in late 1946. His official FBI record shows him as having retired in good standing. That’s where the trail ends.

And now Maryweather is in Nowhere, owns a bank, and is the de-facto social leader in the town. Everywhere I’ve been in Nowhere, and no matter who I talk to, Copeland is a revered father figure. Most of the business owners I’ve interviewed tell of receiving low-interest loans from Copeland’s bank and talk of how lenient Copeland has been concerning repayment. He’s not a thug making a fortune on usury. Sometimes it looks like he doesn’t even care to make money.

A tingling in the back of my brain tells me that there is more to it, and a renegade thought barely brushing my consciousness—just a ghost of a thread of a thought—occurs to me for the first time:

Copeland is Lew Bonaventure.

At first, the idea doesn’t assert itself forward into my thinking, but I recognize that it’s there. Percolating. I top my glass with the deep red house wine and I sit, smoking a Chesterfield and staring at the papers before me.

The thought steps forward and announces itself.

Copeland is Bonaventure. His inheritance money is the gold. There never was any real gold. It was all a ruse because a rich, trust fund spook from Princeton isn’t an attractive enough calling card to draw thousands of people into giving up their lives for no reason and moving out into the desert. It’s like a cult. But there is not one thing about the town that is cult-like. Not a single red flag. Copeland doesn’t preach, isn’t an idealogue, doesn’t tell people what to think or what to say. There is no jail, no secret police, no fear. Copeland doesn’t need money or power and doesn’t seem interested in accumulating either. He hasn’t prevented me from my work in town and among the townspeople. His only belief system seems to be that a lot of people simply want to be left alone to be happy and they should be allowed that freedom without intervention, and I have no evidence at all, not even a suspicion voiced by any of the people, that Copeland has ever done them anything but good. He’s like a philanthropist… if modern philanthropists didn’t also have agendas. And with that thought, I push the whole thing back down and drink more wine.

But it won’t stay down.

But what if it is? What if it is a cult and I just haven’t been smart enough to pick up the signs? What if the people are being manipulated, only very subtly? What if Bonaventure is in it for money or power, only he’s really, really smart? Why isn’t there an outside telephone system? Where is the county and state government here? How does Mr. Laird have fresh tobacco for his pipe, and how does The Brick and Polly’s and Bix’s get fresh seafood in the desert?

I can believe that the gold is all a lie and that Copeland is Bonaventure, but all of my Yankee cynicism and suspicion cannot create a scenario where Copeland is a villain. And if Copeland was some kind of crook or a zealot, he would have looked in the package. He’d care what a reporter was saying to his editor. It just doesn’t add up.

But if Copeland is Bonaventure and the gold isn’t real, then most of the townsfolk have believed a lie. They are here on false pretenses. And that’s a story, isn’t it?

What would Edward Kramer Thompson say?

He’d say “It doesn’t matter. Write it up. If something is destroyed by the truth, then it deserves to be destroyed. Besides, it’ll sell magazines.”

But I need proof. This whole story would be case law for defamation if I were to get it wrong. Just because Copeland is rich, and is a former Hoover goon, doesn’t mean that Lew Bonaventure doesn’t exist or that there isn’t gold somewhere.

At the bottom of the file is a personal note from Thompson, but I can’t bring myself to read it yet. I don’t want to know, and if Thompson is giving me orders, or calling me on the carpet for buying a car or demanding the story before I’m ready to write it, I don’t want to read that yet. I’m not responsible until I read it.

***

A few days later, Ken and Kate meet up for a picnic and decide to walk over to the sandlot to distribute the Mantle autographs. The day is gorgeous, with baby blue skies for a ceiling and the occasional puffy white clouds moving slowly or perhaps sitting perfectly still as the earth moves underneath. Birds sing and flit into the trees playfully as the lovers walk, and then fly down to the sidewalk to peck and sometimes play fight with the other birds who then burst back upwards into the trees before starting the whole ballet over again.

Ken hasn’t yet discussed with Kate anything about his intel on Copeland and has only told her about the baseball cards and the lone, signed baseball which is in the pocket of his slacks as he walks. The children are playing and a boy slides hard into second base, foot raised high like he’s Ty Cobb and is intending to spike the shortstop who covers second base, but he doesn’t have spikes and his foot just pushes the other, smaller boy down and the boy drops the ball and the wannabe Ty Cobb stands up on second and dusts himself off with his hat as he smiles.

Then they see Ken approaching and the boys scream as if in unison that it’s the man who was taught how to bunt by someone who knows Mickey Mantle!

“Mister! Mister! Have you talked to Mickey Mantle? Can you tell us the story of how you learned to bunt? Who was it?”

“Gene Woodling! Gene Woodling,” another boy shouted. “Gene Woodling taught him how to bunt! Teach us again, Mister!”

Ken goes through the lesson again, just like Gene Woodling taught him before the war, and then he distributes the baseball cards to the screams and shouting of the excited boys. There are back pats and handshakes and ‘boy-oh-boy’ smiles as the youngsters look at the cards and squint in the sunlight and even kiss the cards before putting them in their pockets.

Then Ken pulls out the baseball like a magician revealing a rabbit pulled from a hat and shows the ball around, and the screaming reaches a crescendo such that people are coming out on their porches and looking out at the park to see what’s with all the hubbub. Ken announces he’s going to toss the ball to one of the boys, “and if you catch it it’s valuable like gold and you squeeze it hard and you make sure not to ever let it go!” He tells the boys to spread out and they all do and pound their fists into their gloves and shout, “Throw it to me, Mister!” as they sway back and forth, knees bent and ready. Ken hesitates, building tension, then throws the ball to the youngest and smallest boy, the one who Ty Cobb knocked over. The boy’s eyes slam shut and he drops it and another boy swoops in and snatches up the ball, but turns back, smiles, and sticks the prize firmly into the smallest boy’s glove and then the other boys lift the small boy on their shoulders and they do a tour of the bases with the young boy on their shoulders and singing “He’s a jolly good fellow!” and Ken looks over and Kate is crying and dabbing her face with a handkerchief.

“That was really something, Ken,” she says later as they lounge on their picnic blanket and drink Coca-Colas. “You really made those boys happy.” Ken just smiles and they eat fried chicken and wipe their faces with cloth napkins and sip their Cokes. “Maybe we can have a boy someday and I can teach him how to bunt just like Gene Woodling taught me,” Ken says without really thinking about it first.

Kate looks down and she’s crying again, but just a single tear and she says, “Yes. I suppose that would be very nice if that happened.” But she doesn’t ask what he means by it or if he has any plans.

***

“What if there’s no gold?” I ask Kate. It’s later now, near dark, and we’ve packed the basket back into the Packard and driven to Kate’s house and now we’re sitting on the front porch swinging in the swing.

“There is gold.”

“What if there isn’t any gold and there isn’t any Lew Bonaventure either?”

“Well, there is both. So why speculate?” Kate says.

“What if there isn’t?”

Kate sighs. “There is a God even if you haven’t seen him, and just because you haven’t seen Lew Bonaventure, doesn’t mean he doesn’t exist.”

“Have you seen him?”

Kate looked down. “I know he exists, as surely as I know that you exist.”

“But tell me, what would happen to the town if it were to be discovered that the gold story was a hoax? That for some reason everyone had been lied to?”

“It doesn’t matter what foolishness happens, the only thing that would change Nowhere…”

“Is what?”

Kate looked up at Ken, but only for a second. “If something bad was going to happen to the town, I’ve heard the men say they’d rather bulldoze it all than give it over to the world to destroy it. Like something out of that book The Fountainhead.”

Ken lit a cigarette and thought on that. Sounded like nothing but bluster to him, but it did betray the feelings of the people of the town. At least the men.

“Why are you asking me this?” Kate said.

“I’m just trying to see it all the way you see it, Kate. And the way that John Lee sees it. And the way a stranger might see it in Kansas City or Minneapolis. That’s what I do. You know I’m here to write a story.”

“I know,” Kate said. “I guess I just thought—”

Ken stood and walked to the porch railing. “My editor would say that if something can be destroyed by the truth, then it deserves to be destroyed.”

Kate looked him in the face. “But it wouldn’t be the truth, Ken. I told you that Bonaventure exists. The gold exists. I just know it and I wish you’d trust me.”

Ken laughed to break the tension. “What if Steve Durant is right and we’re all already dead?”

Kate smiled. “If that’s true, then let’s go to the Dipsy Doodle and each have four hamburgers. I’m game if you are.”

***

I’ve not intervened much in the story, but I’ve tried to set out events in the same order I found them in Ken Halberson’s notes. But here, I see that Ken is right. He has reached an inflection point, and it is here where—just as Ken became confused by the information he had—his notes can become confusing too. When did things happen and in what order? Was it now that Ken began to ask questions about logistics? I mean, how was a town the size of Nowhere supplied? Ken knew Nowhere wasn’t some self-sufficient homesteading community. There were no large farms in the area. It was all desert out there. The town was a modern, consumer-driven small city, and the logistics involved in supplying the town must have been significant. Was it now when Ken began to investigate Nowhere Trucking and Supply? When was it that he snooped in the yard of the trucking outfit and found out they only had four trucks? And when did he judge that those four trucks would be wholly insufficient to handle the cross-country deliveries that would be required to supply Nowhere even for a single day? If supplies were coming in from Albuquerque, or El Paso, or even Lubbock it would take at least twelve trucks, he reckoned, operating around the clock to cover the miles and to keep supplies flowing. Was it here in May of 1954 when Ken noticed and wrote in his notes that the four trucks operated by Nowhere Trucking had old, tread-worn city tires and he guessed that the trucks had never been out of town? That they had been used for local deliveries only? That the tires would have been shredded if they’d been crossing the desert from Albuquerque regularly where there were no actual roads?

Ken noticed that Nowhere had the best of everything, but where did it all come from? How did hamburgers and Chesterfields and furs and tobacco and oysters and cockatiels and crystal chandeliers get to the middle of the desert with no one noticing?

And the questions kept coming, but where do I, the author, place them on the timeline?

Why is it that Ken never saw an aircraft flying over Nowhere? When did he first notice the byzantine blue sky was never striped by condensation trails from planes, and when did he think of asking about it?

Where did the water supply come from? The electricity? The gasoline for the cars? Ken had seen a gasoline tanker parked in a lot over on Northwest, but he never saw it delivering gasoline to the stations. Maybe it did, but he never saw it.

At some point, Halberson began impromptu, informal interviews of restaurant owners and shopkeepers and he took notes. I’ve mentioned that there are hundreds of thousands of words scrawled on notes in this briefcase. Notes written on everything from receipts to napkins. Some were actually scribbled in notepads, in longhand or shorthand, and later typed by Ken and stapled with business cards. Carlo Rocca, the old, retired drummer with the twisted hands and fresh memories who owned the sweet shop on Crow and still cried over his dead daughter said, “the truck comes on Thursdays.” And Ken staked out the place, chain-smoking Chesterfields and drinking cold coffee one warm pre-dawn. Sure enough, the delivery truck came on Thursday, but it was one of the four Nowhere Trucking trucks and it had never left town because Ken had registered it as being in the truck yard after 2 a.m. But here was the truck being unloaded at 6 a.m. So where did the sugar and canned syrup and five-gallon buckets of glaze and the chocolate powder and clove and cinnamon oil come from? Ken made a note to find out. He also started asking the people he interviewed about Lew Bonaventure. No one that Ken asked about him had ever met the man, except maybe Carlo Rocca, who said he knew him but wouldn’t make introductions. “He’s a private man. He knows you’re here. If he wants to meet you and talk, he’ll let you know.”

Lew Bonaventure, according to the notes, lived in a huge mansion, something (Ken was told) like the Hearst Mansion “but not as ostentatious.” The Bonaventure estate was out on Northwest a half-dozen or more miles out of town, and Ken couldn’t find anyone who’d been there or who would be willing to take him to see the man.

So, at some point, and I don’t know exactly when because the timing is unclear, but at some point, Ken took up the topic of Lew Bonaventure with John Lee Danner. But, before heading over to The Brick hoping to catch John Lee in his cups, Ken finally read the note that had come in the package from Edward Kramer Thompson at LIFE:

Halberson,

It took some doing to get Mantle to sign so many cards AND a baseball, but I put some parallel pressure on Stengel and WPIX, and together they got it done. I hope this kind of thing isn’t to get you laid there. I mean… if it is, then good for you, but at least let me in on the ‘why’ of it. Also, find enclosed the file on your Copeland boy. Ex-spook it seems, but with lots of daddy’s money. If you’re going to slander a millionaire, please give me a heads up so I can resign first. Editors get named in those suits, you know? Oh, and I know nothing of a car. Haven’t seen anything on it, but now I’m curious. Hope you are doing well, Ken, and that you’ll have ten thousand good words for us at some point.

Edward Kramer Thompson, Editor.

Leave a Reply